A People's Cup of Solid Gold

Unveiling the truth behind China's financial system and why the West slanders it

The Cup of Solid Gold (鞏金甌) was China’s first national anthem, adopted in 1911. The Jin'ou (金甌) was a type of golden wine vessel featured in the title of both the anthem and this article, symbolizing a wealthy and “indestructible” country. This article seeks to investigate the wealthy and “indestructible” Chinese economy, an economy which has weathered many regional and global financial crises over the last three decades. The growth and ever-increasing wealth of China’s economy has been to the benefit of China’s people; hence, it is a People’s Cup of Solid Gold. In order understand how China’s economy is so resilient and steadfast in growth, one must first begin with the Chinese state’s involvement in finance.

The nature and extent of the role of the Chinese state’s involvement in the economy is subject to Her political economy. The previous article on RTSG about China’s political economy made a broad sweeping compilation over the nature of the State as a whole, introducing the SOE (state-owned enterprise) and shareholder system. This article in the series will continue investigating the Chinese economy, going more in depth into the way finance and investments are handled by the People’s Republic.

State control of investment remains substantial, so much so that government guided investment mechanisms, state-controlled banking systems, and dominant state-owned enterprises still remain well into Reform and Opening Up. The way these investments are conducted almost perfectly match how investments themselves were conducted under the “Mao era economic system” [1].

To understand the role of the state sector of the economy, it is not enough to just look at what proportion they have of GDP, nor their degree of concentration. It is also important, if not more so, to look at what proportion of investments are channeled through the state sector, because investments are the driving force of the economy. Fortunately, statistics about fixed-asset investments (investments in buildings and machinery) are also much more accurate and uncontested compared to GDP statistics. This article will thus go over the nature of the finance and investment systems in China, its purported effectiveness, and why the West seeks to attack and slander it as somehow being “inefficient”.

Investment Policy

In July 2014, the first two official “state capital investment companies” were established under two CSOEs (Central State-Owned Enterprises): COFCO (a food processing holding company) and SDIC (an investment holding company) [2]. In 2015, a state directive regarding SOE reform supported the diffusion of state capital into non-state enterprises (of which does not necessarily mean private, refer back to the concept of LLCs/Shareholding enterprises in the previous article). For the goal of this state directive was supporting development in public services, high-tech, eco-environmental protection, and strategic industries, in addition to non-state-owned enterprises with large development prospects and strong growth potential. [3]

That state directive also set a 2020 deadline for “decisive achievements” in SOE reform, requiring SOEs to demonstrate progress in “mixed ownership reform.” The deadline may explain why some local SOEs have pursued the purchase of listed, nonstate companies: to provide shells for SOEs to enter new markets and gain control of other companies. According to formal reports from the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges, these kinds of transfers are not large in number, but the trend is a significant one. Since 2016, listed firms have changed their controlling owner from private to state at an average rate of ten per year. This number was as high as 23 firms changing in 2018. Of all of the listed firms that undergo major ownership reforms, the clear trend in 2017 and 2018 is that most of these firms are private, not state-owned (306 in 2018), double the number of privately owned firms to undergo equity transfer in 2017. [4]

In February 2016, two new “state-owned capital operation enterprise” pilots were established within China Chengtong Holdings Group and China Reform Holdings, both asset management holding companies governed by SASAC. Both established multiple funds, with additional shareholders primarily drawn from other SOEs, that provided capital for SOEs to buy listed private firms. By the end of 2018, these two managed total assets of 900 billion RMB. [5]

Another statement released in 2018 stated the objectives for state investment as promoting the rational flow of state-owned capital, optimizing the investment of state-owned capital, concentrating on key industries, key areas and advantageous enterprises in service of national, strategic needs. [6]

State Investment Firms

A study found that the overall ownership of assets within investment firms in 2017 were 46.51% central state owned, 46.18% local state owned and only 7.31% being truly private. The top 20 shareholders within investment firms also find that shareholders of a private origin are the lowest percentage of roughly around 500 or so registered private investment shareholders. With more than 2,000 central SOE shareholders, more than 1,000 “Big-Four” bank shareholders, roughly 500 for both local SOE and "Other" shareholders respectively and around 700 pension funds. So roughly around 10.8% of all shareholders of investment firms are of a private orientation. [7]

The state’s role as owner of firms has narrowed in comparison to the pre-Reform and Opening Up era, but the deployment of state capital has morphed form rather than abated. As we have shown, the state invests broadly in the non-formal state sector to a great degree. Further, the deployment of state capital into the wider economy has accompanied a change in the structure of the state; hundreds of shareholding firms, large and small and owned by local and central levels of the state, now interface extensively with other firms, can intervene with ease in stock markets, and constitute new agents in the execution of the CPC’s overall economic policy.

The largest “private” investment firm is China Minsheng Group. While on paper it is the largest private firm, it was created in the first place with backing from the State Council. According to their 2023 shareholders report, the largest controlling ownership is held by Dajia Life Insurance which is on paper a joint-stock limited company, holding 17.84% of the total shares, the second largest share is 4.18% [9]. However, Dajia Life Insurance is 98.23% owned by a Chinese SOE (China Insurance Security Fund) [10]. Thus, despite it being claimed as the “largest private equity investment company in China”, it is only a formal classification for it to be a joint-stock limited company. The controlling shareholder rights remains squarely in the hands of a SOE.

According to the NYT, China, unlike other economies, has a unique system that facilitates the deployment of investment projects: The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). While other economies can only use fiscal or monetary policies, China is able to use the NDRC to spearhead investment.

The NDRC makes basic decisions as to which industries should receive major government investment. The NDRC is deeply involved in key regulatory decisions and even carries out some of the “classic” regulatory functions of price setting and licensing. It also has been deeply involved in the numerous restructurings of strategic industries, and in 2003, the State Council assigned it responsibility for formulation and oversight of industrial policy. [11]

Using a sample from the NDRC’s 2008 investment capital distribution, the vast majority of investment was skewed towards infrastructure development. 81% of all investments were in the realm of construction. From a period of 2003 - 2013, economic stimulus packages are skewed in favor of the financing of SOEs relative to non-SOEs. [12]

Efficiency of Chinese Investment in comparison to the Western model

It is not merely enough to talk about investment and how the state controls investment, but we must also demonstrate that this investment system is, in fact, superior to the system employed in Western countries. State investment is well and good, but if it is more inefficient or inferior to ones employed by private dominated systems, then naturally there is something wrong with it. There should be no empty talk or hand waving, the next segment will go into explaining how China’s state investment system is, in fact, superior.

The 2008 Great Financial Crisis

An example of this superiority would be how China dealt with the 2008 financial crisis. The Chinese leadership was forced to deal with the effects of the worst capitalist crisis since World War 2. When the crisis hit in 2008 to 2009, many tens of millions of workers in the U.S., Europe, Japan and across the liberal world were plunged into unemployment. China, which exported to the liberal-capitalist West, was faced with the shutdown of thousands of factories, primarily in the eastern coastal provinces and the special economic zones.

However, the prominent Western researcher on China and Washington think-tank pundit Nicholas Lardy found the following:

“In a year in which GDP expansion [in China] was the slowest in almost a decade, how could consumption growth in 2009 have been so strong in relative terms? How could this happen at a time when employment in export-oriented industries was collapsing, with a survey conducted by the Ministry of Agriculture reporting the loss of 20 million jobs in export manufacturing centers along the southeast coast, notably in Guangdong Province? The relatively strong growth of consumption in 2009 is explained by several factors. First, the boom in investment, particularly in construction activities, appears to have generated additional employment sufficient to offset a very large portion of the job losses in the export sector. For the year as a whole the Chinese economy created 11.02 million jobs in urban areas, very nearly matching the 11.13 million urban jobs created in 2008.

Second, while the growth of employment slowed slightly, wages continued to rise. In nominal terms wages in the formal sector rose 12 percent, a few percentage points below the average of the previous five years (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2010f, 131). In real terms the increase was almost 13 percent. Third, the government continued its programs of increasing payments to those drawing pensions and raising transfer payments to China’s lowest-income residents. Monthly pension payments for enterprise retirees increased by RMB120, or 10 percent, in January 2009, substantially more than the 5.9 percent increase in consumer prices in 2008. This raised the total payments to retirees by about RMB75 billion. The Ministry of Civil Affairs raised transfer payments to about 70 million of China’s lowest-income citizens by a third, for an increase of RMB20 billion in 2009 (Ministry of Civil Affairs 2010)” [13]

The key takeaway is the rise of investment, which is what allowed China to offset the damage caused by the 2008 Great Financial Crisis; something that the United States and other Western economies have been unable to replicate, as will be showcased below using data from the OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) and United States.

During the period from the first quarter of 2008 to the fourth quarter of 2009 OECD GDP fell by $1.04 trillion dollars in constant parity purchasing power (ppp) terms - the form in which the OECD aggregates data. Of this fall $0.99 trillion, equivalent to approximately 96 percent, was accounted for by a decline in fixed investment. [14]

In the case of the USA, from 2004 - 2008, 61% of its total GDP comes from capital formation/investment. However, in the 4th quarter of 2007, and the 2nd quarter of 2010, the monetary value of US personal consumption has risen from 69.9% of GDP to 70.5% and total US consumption has risen from 85.8% of GDP to 87.6%. [15]

However, once we look at China, we find that not only did investment not fall, unlike in OECD economies or the United States. Rather, investment in fact rose significantly. Inventories rose by 0.1 trillion, government consumption by 0.8 trillion, household consumption by 2.6 trillion, and fixed investment by 5.3 trillion, which offset the decline in net exports of 0.8 trillion. The increase in fixed investment was equivalent to 67% of the increase in GDP and the increase in household consumption to 33%.

State fixed investment in the US was only 3.5% of GDP. This was too small a base from which to reverse the consequences of the scale of decline in private fixed investment that had occurred. It is precisely because the US and other OECD states lack a substantial state finance system that it was unable to raise sufficient capital to offset the decline in investment. Meanwhile for China, investment can therefore be decelerated to slow down an overheating economy, as in 2007, or increased to stimulate investment to counter economic downturn - as in 2008. [16]

The 2020 COVID Financial Crisis

In similar vein to the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, there was a substantial increase in household consumption, of $2,970 billion. Government consumption also rose by $581 billion. Gross fixed capital formation also rose, by $838 billion, but this was insufficient to offset fixed capital depreciation of $848 billion. Therefore, U.S. net fixed capital formation fell by $10 billion. [17]

Compared with China, it is in fact the opposite. Fixed investment grew significantly and was the biggest contributor to GDP growth, and unlike the USA, overall net fixed consumption didn’t dip into the negative. This almost mirrors the 2008 financial crisis 1:1, the USA being unable to foot the bill when it comes to a sharp drop in investment, while China is able to raise a large amount of investment to counteract the effects. [17]

During the peak of the COVID-19 crisis in 2020 and during the economic slowdown of 2022, the increase in private investment fell to very low levels, 1.0% in 2021 and 0.9% in 2022. But overall fixed investment remained significantly higher—2.9% in 2020 and by 5.1% in 2022. The reason for this was that in those years China’s state investment was greatly increased, a rise of 5.3% in 2020 and 10.1% in 2022. This produced a strong anti-cyclical effect in preventing a more severe decline in investment. In contrast, during 2021, when the economy was recovering and private investment was rising relatively strongly, the rate of growth of state investment was reined back to 2.9%. [17]

Compared with China, in 2022, only 16% or less than one-sixth of all U.S. fixed investment will originate from state institutions. These government investments only account for 3.4% of GDP. Given the extremely small scale of U.S. state-owned economic institutions, even a high proportion of U.S. government investment cannot prevent the overall decline in U.S. fixed investment—to offset a 10% decline in private investment, U.S. government investment must increase by 50%. [17]

The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis

In the 1996-1998 period, many financial attacks came for the “Asian Tiger” economies. These countries had been attracting foreign investment in order to become manufacturing hubs, and to do so they had offered up dollar pegs. Private Western investors went one by one through Thailand, Indonesia, South Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, etc. betting that these governments could not maintain their dollar pegs and would have to float and devalue their local currencies. This came to be known as the “1997 Asian Financial Crisis.” [18]

China on the other hand, who had not been pressured by the IMF to liberalize or open up their capital markets were shielded from these events. Although China had long been advised by prominent Western economists and pressured to lift its capital controls and enact a range of other deregulatory reforms, it had refused to do so. As a result, it had been able to weather the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis storm. [19]

However, the storm was not over yet. In 1998, the infamous liberal financier and billionaire hedge fund manager, George Soros, decided to make a beeline for Hong Kong. Hong Kong was known as the “liberal pocket” of China that was open to financial speculation, and was one of the few Asian markets not yet ravaged by Soros and other predatory hedge fund sharks. At the time, Hong Kong was transferred back to China for less than a year before trouble showed up to its shores. On August 13, 1998, the HSI (Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index) fell by more than 60 percent to 6,660 points. Hong Kong's property market deflated by half and the GDP shrank 5.5 percent. The Chinese government repeatedly pledged that the RMB (¥) would not be devalued. At a press conference in March, then Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji promised that the central government would protect Hong Kong from the financial crisis “at all costs.” With the assistance of Beijing’s state-owned banks, nearly 10 million USD was plowed into the market, stabilizing and protecting it from the speculatory attacks from finance sharks and banksters led by Soros. [20]

George Soros was forced to walk away with losses. He later admitted in 2001, that the local monetary authorities did a good job in preventing the collapse of the Hong Kong market. The precise way that China avoided this speculatory attack was through its strict state-set capital controls and its state-owned financial system. At a meeting in December 1997, then Vice Premier Zhu Rongji told Chinese central bankers and financial executives that the country was fortunate not to have been involved in the Asian financial crisis, highlighting that state regulation of the financial system had been key. [21]

Without a large comprehensive state-owned financial system supporting Hong Kong, the Hong Kong market would have gone under and been subject to the Asian Financial Crisis, which had ravaged many other Asian nations. This segways into the next subject in this overview of finance in China: the state-owned financial system itself.

The State-Owned Banking System

The retail banking industry in China has some of the largest publicly listed banks in the world co-existing with hundreds of thousands of less-regulated rural co-operative institutions. The present Chinese banking industry are regulated by the “Big Four”: the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), Bank of China (BOC), China Construction Bank (CCB), and Agricultural Bank of China (ABC). All four of the “Big Four” are state-owned lenders. [22]

There are four kinds of banking institutions in China: market-oriented banks, policy-oriented banks, city commercial banks, and rural financial institutions. Market-oriented banks are overwhelmingly state-owned, being known as state owned commercial banks, but they are still listed on the stock market. These banks include the aforementioned ICBC, ABC, CCB, etc. [24]

Then there are policy-oriented banks, which are designed to help the government achieve its long-term goals in areas where profit-driven banks might be reluctant to lend. The government can also use them to raise investment or boost economic spending to prevent a financial collapse/slump (refer back to the previous section above, Efficiency of Chinese investment in comparison to the West).

Major examples of policy banks include the China Development Bank (CDB), Export-Import Bank of China (Eximbank) and the Agricultural Development Bank of China (ADBC). The CDB is used for Infrastructure, urbanization, industry upgrade and equipment manufacturing, poverty relief and development. Eximbank is used for foreign trade and cross-border investment, “Belt and Road” infrastructure projects abroad, helping small- and medium-sized companies “go global”. And lastly the ADBC is used to finance the building of reserves of key agricultural products, rural infrastructure, shantytown redevelopment, and agricultural firms. In 2014, the CDB was used to prop up the economy due to a stock market downturn, which stabilized the economy and fueled shantytown renovation. [25]

The third type of banks are the aforementioned city commercial banks which are majority owned by respective local governments, with occasional joint-ventures with private or foreign investors. Their main goal is to provide loans for small to medium businesses and to stimulate the local economy. The same is to be said for rural financial institutions, which function and operate the same way, but serve rural regions. [26]

Interestingly, 87% of profits generated by China's banks were funneled back into the “real economy”, a big portion in the form of dividends was distributed to state-owned entities, which acted as fiscal spending/investment in the real economy. Another to citizens via stock. Retained capital indirectly supports the real sector by leveraging credit and bond purchases to the real sector again. [27]

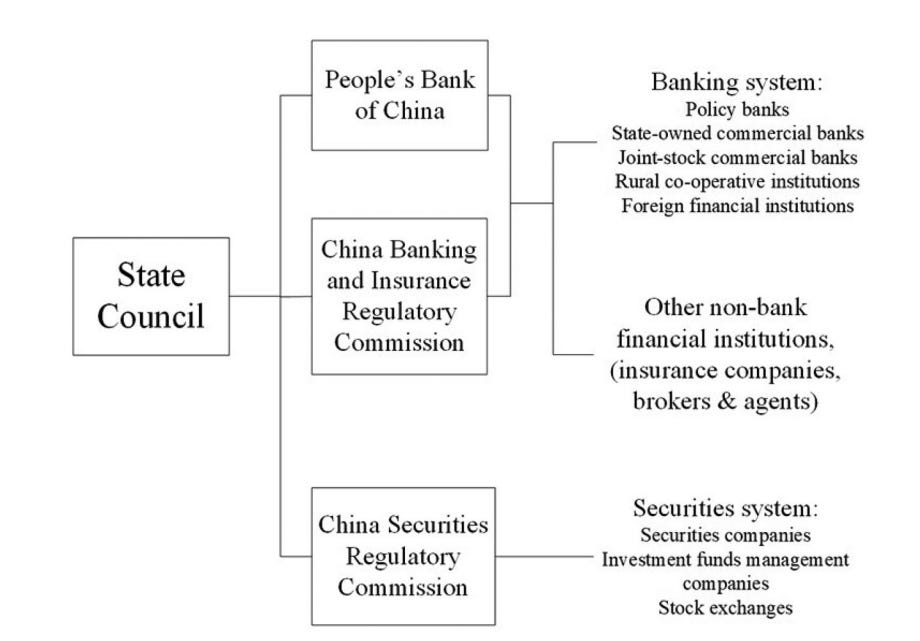

Overall, all bank managers are appointed by the CPC, with commercial banks subject to credit quotas and ultimately, all the banks are subject to control from the Chinese state council as seen in the diagram posted previously [28]. The amount of private involvement is highly exaggerated. As of the end of 2017, there are only 17 private-owned banks among 4,532 financial institutions classified as the banking industry. The number of people employed by these 17 private-owned banks only accounts for 0.1% of all banking staff. [29]

But how do these banks compare to the West’s? In the next section below, the effectiveness of China’s state-owned banking system will be compared to the liberal profit-oriented model prevalent in the West.

Effectiveness of the Chinese banking system relative to the West

To use the metric of return on assets (ROA) and liquidity ratios to measure the effectiveness of China’s state-owned banking system is ultimately meaningless. This is because Chinese banks take on the means primarily resembling development banks. In turn, this system has an overall positive impact in the long term, despite not having the myopic short termism of Western commercial profit-oriented banks. This is due to the ability of long-term funding at low interest rates being key for the sake of large-scale infrastructure construction, which in turn is vital for long term economic development. [30]

Even then, we can attempt to use the insolvency metric to judge whether the Chinese banking system is efficient or not. The solvency ratio of non-performing loans to GDP ratio of state-owned commercial banks was 13.8% in 1993 but rose to 18% in 1997. [31]

State-Owned Commerical Banks (SOCBs) clearly behave more like their development bank counterparts elsewhere by providing counter-cyclical lending to stabilize the external economic shocks and provide long-term financial support. These loans are crucial to mitigating external shocks and stabilizing the Chinese economy (such as during the Great Financial Crisis in 2008). [32]

The Return on Assets (ROA) for Chinese State-Owned Banks since 2010 - 2019 have been consistent at 0.91 - 1.09%, which is much higher than in comparison to Foreign Banks which average at 0.45 - 0.78%. The ROA for three of the biggest four commercial banks in the US (Bank of America, Citigroup, and Wells Fargo) was comparable, at 0.92–1.08 in 2019. Only J. P. Morgan Chase, with an ROA of 1.27, had a higher yield than the SOCBs in China. The graph below illustrates the aforementioned ROA percentages. Note, for laymen, ROA refers to how efficient a company's management is in generating profit from their total assets on their balance sheet. It is calculated using net profit divided by total assets. [33]

In 2019, the Non-Performing Loan ratio of SOCBs had increased to 1.86 percent. In comparison, it was 0.67 percent for the foreign banks incorporated in China, 1.38–1.64 percent for JSCBs and city commercial banks, and 3.09 percent for rural commercial banks (slightly higher than the 1.5 percent for banks in the US but much lower than the 3.41 percent in the EU). Note, Non-Performing Loans refers to loans that the debtor is unable to pay back, meaning the borrower is unable to pay back the loan in full. [33]

So, economics jargon and terminology aside, what does all of this mean? J. P. Morgan Chase Bank having a higher ROA (more efficient in generating profit) than Chinese State Banks is unsurprising as it is one of the world’s largest for-profit banks. Though surprisingly Chinese State Banks still outperform most of the world’s other banks despite operating as aforementioned development banks - that is most loans going towards productive means such as infrastructure construction. Loans in the US on the other hand typically go towards parasitic means such as homeowner mortgages.

This leads into the second bit: the Non-Performing Loan Ratios (NPLRs). The EU having a higher ratio of 3.41% means that the EU, in comparison to China and the US, have the highest rate of loans that may likely never be paid-back. It is a slight blemish on paper that China’s SOCBs have slightly higher ratios than the US (1.86% vs. 1.5%). Though, it should again be stressed that these loans usually go towards productive infrastructure projects, in comparison to the parasitic nature of loans in the US that prey on individuals such as via student loans or housing mortgages. Why? Despite the fact that a few of these loans are unable to be paid initially, they end up paying for themselves in the long-run due to the benefits of said-infrastructure construction. Thus, this is why comparisons between Western and Chinese state-banks’ ROAs and NPLRs doesn’t really matter due to the fundamental difference in the function and methods of operation of the two systems.

Chinese Capital Markets

The way the stock and bond markets are set up in China are very interesting, because they are one of the only stock markets where the State is the ultimate regulator and controller. The central government plays every role from issuer, to underwriter, to regulator, to controlling investor and manager of the exchanges. Efforts to simplify domestic arrangements have served only to conceal the fact that the state in its many guises still owns nearly two-thirds of domestically listed company shares. The combination of state monopolies with “Wall Street expertise” and international capital has led to the creation of national companies that represent little more than the incorporation of China's old Soviet-style industrial ministries. [34]

While all states certainly have the objective to prevent the build-up of financial risk or overspeculation, what sets China apart is the constant intervention into and active management of capital markets through its state-owned exchanges. Chinese markets are the only markets where the exchanges don’t encourage speculation; because they are worried about the risk. In the words of Charles Li, CEO of the Hong Kong Exchange (HKEx): “while Europe is struggling with MiFID II, in China you have MiFID 10”, referring to EU market regulatory laws (the MiFID II). [35]

In Chinese stock markets, market data only comes as snapshots (2–4 times per second), while direct market access or co-location are not allowed. As a result, no speed asymmetries exist between investors and transaction volumes are decreased. In futures markets, high volume trading is allowed but restricted. While co-location is possible, direct market access is not, so that every trade that enters an exchange has to go through a Chinese broker (foreign brokers are prohibited from operating in China). This also creates responsibilities for brokers to ensure their members’ compliance as rule violations would fall back on them. This creates a ‘see-through monitoring system’, allowing Chinese exchanges to trace every single trade to the original investor (and a Chinese ID card). [35]

Meanwhile, to compare with global markets, global markets such as those in the US, Europe, etc. have a constant stream of information which allows infrastructure to have high volume trading. This provides advantages for those professional traders who can operate faster trading systems and are able to co-locate their servers in exchanges’ data centers or get direct market access. [36]

A key difference that China has in comparison with global markets, is the division of shares into 3 unique types: A-Shares, B-Shares and H-Shares. A-Shares are shares of companies based in mainland China that are listed on either the Shanghai or Shenzhen stock exchanges, that are off limits to foreigners. H-shares represent the shares of public companies from mainland China that are listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, these are open access to foreign investment. B-shares are less well known but are just shares accessible to foreign investors that are typically quoted in foreign currencies. [37]

Another negative aspect of stock markets can be the phenomena known as financialization, where insufficient funding is being diverted to the material economy, instead merely circulating in finance. One phrase that is often invoked by Chinese authorities is that finance should serve the real economy and that “serving the real economy is the bounden duty and purpose of the financial sector.” [38]

The Chinese exchanges try to ensure prevention of financialization through their contract specifications; strict position limits and hedging quotas play an important role here. Almost all contracts on Chinese futures exchanges need to be physically delivered. This is in contrast to international markets where almost all contracts are cash settled as there is no mandate or interest to actively encourage actual commodity trading. The Chinese exchanges also engage in many educational activities to get commodity companies, e.g. steel mills, mining, energy or food-processing companies, to hedge their risk in commodity markets. For laymen, hedging means using investment strategies to limit risk of loss in financial assets due to price fluctuations. [39]

Chinese exchanges are also aiming to assist national development goals by facilitating China’s (commodity) pricing power. As commodity futures prices are used as reference points for physical trading, the Chinese exchanges aim to gain sufficient market share to gain benchmark status and thereby have a say in the global pricing of commodities. Free market advocates would argue that these prices are set by markets and that it is “unethical” that China wants to have a say in commodity pricing. [39]

While internationally the main function of stock markets is for companies to raise money, most exchange-listed companies in China are state-owned enterprises (SOEs) with sufficient funding from state-owned banks. The state’s role is also not diminished through the (often only partial) listing of SOEs – its control instead changed from direct ownership to often becoming the largest shareholder. [40]

It cannot be emphasized enough that the level of control the Chinese state has over the stock market is unprecedented. During the 2015 stock market downturn, out of fear of a crash, the Chinese equity market was shut down basically overnight. Between 25 August and 2 September 2015, CFFEX increased pre-fundable margins from 10 to 40 percent, raised intra-day execution fees 100-fold to 23 basis points, lowered position limits from 500 to 10 contracts per day, investigated non-complying investors and suspended them from trading. Such a massive market intervention through state institutions would be very unlikely and hardly possible in global finance. [41]

If there is too much speculative trading in a product, the exchanges will increase intra-day execution fees or intraday margins for those contracts. Further, they will call top-traders or their brokers, telling them to stop trading for the day. Non-compliance can also be punished by the exchanges – trades can be annulled (or in rare cases even declared illegal), retrospectively. Investors receive warnings, and when violating rules repeatedly, can even be banned from trading for a certain period or lose their trading license altogether. These harsh measures have a “proactive preventive/preemptive effect”, stopping these things from happening in the first place. [43]

Of course, this risk management is not always effective as demonstrated by the 2015 stock market crash. But failing to prevent overspeculation has severe consequences for exchange personnel. After the 2015 crash, for instance, several high-level exchange and regulatory executives were ousted, most prominently CSRC Chairman Xiao Gang. [44]

Speaking of the 2015 crash, stock market returns in both developed economies, such as the US, UK, Japan, Korea and Taiwan, and large emerging economies, such as South Africa and Brazil, are strong predictors of GDP growth in the following year [44]. The correlation between market returns and future GDP growth for China, however, is much lower and statistically insignificant. This meant that while there was indeed a crash in 2015, there was negligible effect on GDP growth [45]. And as mentioned earlier in the State-Owned Banking System section, the China Development Bank (CDB) was used to prop up the economy due to a stock market downturn, which stabilized the economy and fueled shantytown renovation. [46]

Interestingly, from 2017-2022, the US's GDP grew 12.6% while the New York Stock Exchange growth rate was 50.70%. During the same 5-year time frame of 2017-2022, China's GDP grew by 33.2%, while the Shanghai Stock Exchange growth rate was 16.94%. This clearly indicates that there is a disconnect between the stock market’s performance in China, and with GDP growth rate.

Despite the fact that the SSE grew only 16.94% while China’s GDP grew 33.2%, the inverse is true of the USA with the stock exchange growth outstripping GDP growth x4 over. While China’s GDP outstripped the SSE’s growth x1.9 times.

In summation, China is the only country with a capital market that actively discourages speculation, insider trading, and market manipulation to the extent that it is capable of shutting down an entire stock exchange on a whim. The regulatory systems in place in China are far more advanced than global norms, indicating a much more extensive reach of control and influence over the pace of the stock market. This demonstrates the power of China’s Marxist-Leninist planned/interventionist economic model.

Why does the West attack China’s Finance and Investment System?

The reason why the West continues to deride and try to convince people China’s economic system is somehow “inefficient” or somehow “unable to grow” or will “begin to decline”, is because Western economics is fundamentally based on illogical terms in regard to long term growth prospects for the masses.

According to economic think-tank Goldman Sachs, China’s GDP growth will fall to 3.5% by 2027 and 2.5% by 2032 for a 10-year annualized growth rate of 3.4%. This claim is somehow substantiated that Capital formation/Investment as a % of GDP will decline from 42% in 2022 to 35% in 2032. [47]

What sort of “proof” is this? Why would China commit economic suicide by deliberately shrinking their capital investments? This fall in investment accounts for 92% of the decline in the GDP growth rate, only 8% of the decline the Goldman Sachs report projects, or 0.2% GDP growth a year, is attributable to factors other than the decline in investment. Without the investment decline, the Goldman Sachs report’s data shows that China’s annual GDP growth would only fall from 6.0% to 5.8%.

The only evidence they give for why this will be the case is because as China transitions towards an upper middle economy, it will somehow “adopt” the norms of an upper middle economy by reducing investment as a % of GDP to 34% to match said economies [47]. But why would China do this? This is some bizarre logic; why would China, a much more successful country, follow the economic policies of the unsuccessful?

In truth, many Western economists are blind to the fact, or at least unwilling to admit the fact, that the number one contributor to economic growth is capital formation.

As we can clearly see from the above diagram, for advanced economies, capital makes up 55% of its GDP growth. And for developed economies, it makes up 58%. The largest contributing factor to GDP growth, is evidently, capital formation. While Western economists have a tendency to overfocus on or overrate the role of Total Factor Productivity as the driving force of economic growth, this is not the case.

In G7 economies, investment in tangible assets is the most important source of economic growth. In terms of medians for these 41 economic sectors (i.e. steel, lumber, ferrous mining, etc.) the typical contribution from intermediate inputs was 1.2 percentage points, compared to 0.5 percentage points from capital and 0.3 from labor inputs. This analysis shows that intermediate inputs play a critical role in explaining economic growth. Investment in tangible assets is the second most important source of growth of output across U.S. industries. [49]

Capital accumulation was the primary driver of Developing Asia’s lead over other parts of the world in terms of economic growth. The pattern of rapid growth driven by intensive capital investment is consistent over time and robust to different types of economies in terms of size, location and level of development. The pattern showing the stronger expansion of fixed investment relative to GDP was even more notable for China, which was the most rapidly growing economy in the region during 1990-2010. [50]

The importance of capital accumulation as the driving force for economic growth is not unique to Asia but pervasive worldwide. This source of growth is important not only for developing countries, in which the capital stock per capita is low, but also for developed nations, in which the capital stock per capita is relatively high. For the G7 economies, investment in tangible assets was the most important source of economic growth and the contribution of capital input exceeded that of total factor productivity (TFP) for all countries for all periods examined. [50]

The growth strategy of many advanced economies emphasizes innovation, which has been quite satisfactory prior to the Great Financial Crisis, but neglects investment in human and non-human capital, which continues to fall. [51]

In Western economist circles, the role of TFP is enshrined and individual entrepenurship is seen as the driving factor of economic growth. But as already seen TFP increase, even taken as a whole, is a small part of economic growth, in both advanced and developing economies total TFP increase accounts for less than 23% of the total growth. Since TFP growth is no higher in advanced economies, where individual entrepreneurship is supposedly concentrated, than in developing economies.

Even if the role of ‘individual entrepreneurship’ accounted for the whole of TFP growth in advanced economies — which is a wholly unreasonable assumption given the key role of technology, scale of production, research & development, and other factors — it would be only one third as important as growth in labor inputs and only one sixth as important as growth in capital investment. Attempting to create economic growth based on TFP increases, let alone “individual entrepreneurship”, is like attempting to drive forward a machine using only a tiny gear wheel, while not attempting to shift it using the far larger gear wheel of capital investment or even labour inputs. For simple quantitative reasons such a strategy evidently cannot succeed. [48]

While fixed capital investment is the most important “Solow factor” of production, it is only the second most important driver of economic growth. The most important factor is the growth of intermediate products – the outputs of one industry used as inputs into another. For example, the output of the microprocessor industry (a microchip) is an input into computers. The microchip is an example of an intermediate product, while a computer is a final product. Another example is the production of motor engines, an input into the automobile industry etc. Alternatively, intermediate products are known as material inputs or intermediate inputs. [53]

It is not only in G7 economies that intermediate inputs play the most important role, as for South Korea, the relative magnitude of contribution to output growth is in the order of intermediate material inputs, capital, labor, TFP, then lastly energy. [54]

For Taiwan, it is the same, with material intermediate inputs being the largest contributor to growth from 1981 - 1989, with the exception of seven industries: mining, food and kindred products, apparel, petroleum and coal products, electrical utility, finance, insurance and real estate. [55]

The contribution of intermediate input is by far the most significant source of growth in output. The contribution of intermediate input alone exceeds the rate of productivity growth for thirty-six of the forty-five industries for which we have a measure of intermediate input. [56]

Though it should be noted that although intermediate products and capital are traditionally treated separately, nevertheless, from a fundamental accounting point of view this is not correct. Functionally speaking, intermediate products are just another form of capital, albeit one that depreciates fully in production. [57]

Intermediate products are inputs used up in a single production cycle whereas fixed investment is capital used up (depreciated) across several production cycles. The distinction in Western growth accounting between two different forms of capital (intermediate products and fixed investment) is reflected in Marxist terminology in the distinction between “circulating capital” and “fixed capital”.

The rise of the US to supplant the UK as world hegemon was precisely due to this rise in investment. The rate of US domestic investment was nearly twice the UK level for the sixty-year period of 1890-1950. Its level of capital stock per person employed was twice as high as that of the UK in 1890, and its overwhelming advantage in this respect over all other countries continued until the early 1980s. [58]

In short, in order of descending importance to GDP growth is intermediate inputs, capital formation, labor inputs, and then finally, total factor productivity. This means that reality thoroughly debunks the Western economic consensus that it is “individual entrepreneurship” and total factor productivity growth that drives the economy forward.

This is why the West seeks to deride China’s economic system. Yet, judging from information at hand, this is unlikely to happen. Unless China is somehow overtaken by Western comprador forces that seek to liberalize the country, the rate of investment is not going to fall, but stay stable at its current position. As Marxists, we should seek truth from facts. Evidence has told us that unlike the common position in Western neoclassical economics, it is not Total Factor Productivity that is the largest contributor to growth, but rather, Capital formation.

This is precisely why China’s system is superior to the West; it has refused to listen to Western pundits from the IMF and Goldman & Sachs, unlike the “Asian Tigers”. China has persisted in capital controls and use of high rates of investment/capital formation to stimulate its economy.

Conclusion

In short, the success of China’s finance system and investment pattern is understated. The myths about Chinese economic collapse all hinge upon the premise that China is somehow going to worsen/damage its own economy by reducing the role of investment. Facts have shown us that the largest contributor to economic growth is in fact capital formation/investment, meaning that a low capital formation rate is bound to cause a low economic growth rate. The reason why China’s economy is able to be stable and avoid the damages of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 and the COVID Crisis of 2020 was precisely because it was able to draw up large amounts of State investment to offset the decline in private investment. The Chinese State’s unique abilities to launch such unprecedented, massive economic interventions to prevent its economy from going under is owed to its Marxist-Leninist background and economic traditions. The fact China has been able to weather so many economic storms that had otherwise ravaged many of its peers regionally and globally is itself another successful chapter in the history of Marxism.

Bibliography

Introduction

[1] Loren Brandt and Thomas G Rawski (2011). China’s Great Economic Transformation. Cambridge University Press. p. 353.

Investment Policy

[2] SASAC Held Press Conference on the ‘Four Reforms’, SASAC.

http://www.sasac.gov.cn/n2588020/n2588072/n2591426/n2591428/c3731034/content.html.

[3] Guiding Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on Deepening the Reform of State-owned Enterprises, gov.cn.

https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2015-09/13/content_2930440.htm.

[4] Li Yifang (2019). “Increase in A Share Equity Transfer: Reason, Features, and Policy Recommendations.” (A 股股 权转让大增的特征、原因及政策建议). Shanghai Securities Research Report (上证研报). Number 8, pp. 2, 9.

[5] Li Yifang (2019). “Increase in A Share Equity Transfer: Reason, Features, and Policy Recommendations.” (A 股股 权转让大增的特征、原因及政策建议). Shanghai Securities Research Report (上证研报). Number 8, p. 16

[6] State Council suggestions on implementing the pilot program in promoting state-owned capital investment and operating companies, gov.cn.

http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2018-07/30/content_5310497.htm.

State Investment Firms

[7] Hao Chen and Meg Rithmire (2020). The Rise of the Investor State: State Capital in the Chinese Economy. p. 9.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-020-09308-3.

[8] Hao Chen and Meg Rithmire (2020). The Rise of the Investor State: State Capital in the Chinese Economy. p. 10.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-020-09308-3.

[9] China Minsheng Bank Annual Report, 2023. Hong Kong Exchange News. p. 374.

https://www1.hkexnews.hk/listedco/listconews/sehk/2023/0421/2023042101907.pdf.

[10] BUSINESS COOPERATION FRAMEWORK AGREEMENT FOR AGENCY SALES OF FINANCIAL PRODUCTS WITH DAJIA LIFE INSURANCE CO., LTD. Hong Kong Exchange News. p. 6.

https://www1.hkexnews.hk/listedco/listconews/sehk/2023/0131/2023013101076.pdf

[11] Margaret Pearson (2005). The Business of Governing Business in China: Institutions and Norms of the Emerging Regulatory State, Vol. 57, No. 2. p. 305.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/25054295.

[12] Liu Qigui, Xiaofei Pan, and Gary G. Tian (2016). To what extent did the economic stimulus package influence bank lending and corporate investment decisions? Evidence from China. pp. 1, 7.

https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1979&context=buspapers.

Efficiency of Chinese Investment in comparison to the Western Model

2008 Financial Crisis

[13] Nicholas Lardy (2011). Sustaining China’s Economic Growth after the Global Financial Crisis. p. 23.

[14] John Ross, Li Hongke, and Xu Xi Chi (2010). The Great Recession' is actually 'The Great Investment Collapse.

https://ablog.typepad.com/keytrendsinglobalisation/2010/06/the-great-recession-is-actually-the-great-investment-collapse-by-john-ross-li-hongke-and-xu-xi-chi.html.

[15] John Ross (2010). US economy - the combination of structural slowdown and cyclical recession.

https://ablog.typepad.com/keytrendsinglobalisation/2010/08/us-economy---the-combination-of-structural-slowdown-and-cyclical-recession.html.

[16] John Ross (2010). Why did China’s stimulus package succeed and those in the US fail?

https://ablog.typepad.com/keytrendsinglobalisation/2010/11/why-did-chinas-stimulus-package-succeed-and-those-in-the-us-fail.html.

2020 COVID Financial Crisis

[17] John Ross (2023). Why China’s socialist economy is more efficient than capitalism.

https://mronline.org/2023/06/06/why-chinas-socialist-economy-is-more-efficient-than-capitalism/.

The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis

[18] A. B. Abrams (2019). Power and Primacy: A History of Western Intervention in the Asia-Pacific. p. 379 - 381.

[19] A. B. Abrams (2019). Power and Primacy: A History of Western Intervention in the Asia-Pacific. p. 394 - 395.

[20] Zhou Minxi (2019). How Hong Kong survived the 1998 financial crisis, CGTN.

https://news.cgtn.com/news/2019-08-14/How-Hong-Kong-survived-the-1998-financial-crisis-J9lwvZrsNq/share_amp.html.

[21] Zhou Xin (2016). How Beijing and Hong Kong sent billionaire George Soros packing the last time he attacked Asian markets, South China Morning Post.

https://archive.ph/58Ujs.

State-Owned Banking System

[22] China Focus: "Big Four" banks in full drive to build China into a financial powerhouse, Xinhua (2023).

https://english.news.cn/20231207/97e4a3a11e044ff69dccf7dcf7c0f39f/c.html.

[23] Godfrey Yeung (2020). Chinese state-owned commercial banks in reform: inefficient and yet credible and functional? p. 8.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341892570_Chinese_state-owned_commercial_banks_in_reform_inefficient_and_yet_credible_and_functional.

[24] Godfrey Yeung (2020). Chinese state-owned commercial banks in reform: inefficient and yet credible and functional? p. 9.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341892570_Chinese_state-owned_commercial_banks_in_reform_inefficient_and_yet_credible_and_functional.

[25] What Are the Policy Banks China Uses to Spur Economy? Bloomberg (2022).

https://archive.ph/DrsYd#selection-3453.0-3460.0.

[26] Godfrey Yeung (2020). Chinese state-owned commercial banks in reform: inefficient and yet credible and functional? p. 8, 9.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341892570_Chinese_state-owned_commercial_banks_in_reform_inefficient_and_yet_credible_and_functional.

[27] Qiu Guanhua (2020). Where Did the Bank Profits Go? Banking Industry Special Report. Zheshang Securities Co. Ltd.

https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202008111397820291_1.pdf?1597145108000.pdf.

[28] James Dorn (2015). China’s Financial System: the Tension between State and Market.

https://www.cato.org/commentary/chinas-financial-system-tension-between-state-market.

[29] Kerry Liu (2021). The Rise and Fall of China’s Private Sector: Determinants and Policy Implications. p. 8.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3921568.

Effectiveness of the Chinese banking system relative to the West

[30] James Laurenceson and J. C. H. Chai (2001). State Banks and Economic Development in China. p. 1.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.727.

[31] James Laurenceson and J. C. H. Chai (2001). State Banks and Economic Development in China. p. 11.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.727.

[32] James Laurenceson and J. C. H. Chai (2001). State Banks and Economic Development in China. p. 15.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.727.

[33] James Laurenceson and J. C. H. Chai (2001). State Banks and Economic Development in China. p. 18.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.727.

Chinese Capital Markets

[34] Carl Walter (2014). Was Deng Xiaoping Right? An Overview of China's Equity Markets. p. 18.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jacf.12075.

[35] Johannes Petry (2020). Financialization with Chinese characteristics? Exchanges, control and capital markets in authoritarian capitalism. p. 9.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03085147.2020.1718913

[36] Donald MacKenzie (2018). ‘Making’, ‘taking’ and the material political economy of algorithmic trading.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03085147.2018.1528076

[37] H-Shares vs. A-Shares: What's the Difference? Investopedia.

[38] China Focus: Financial reform plans unveiled to serve real economy in sustainable manner, Xinhua (2017).

http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-07/16/c_136446619.htm.

[39] Johannes Petry (2020). Financialization with Chinese characteristics? Exchanges, control and capital markets in authoritarian capitalism. p. 15.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03085147.2020.1718913.

[40] Yingyao Wang (2015). Rise of the ‘shareholding state’: financialization of economic management in China. p. 10.

https://academic.oup.com/ser/article-abstract/13/3/603/1670234.

[41] Johannes Petry (2020). Financialization with Chinese characteristics? Exchanges, control and capital markets in authoritarian capitalism. p. 10.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03085147.2020.1718913.

[42] Johannes Petry (2020). Financialization with Chinese characteristics? Exchanges, control and capital markets in authoritarian capitalism. p. 11.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03085147.2020.1718913.

[43] Johannes Petry (2020). Financialization with Chinese characteristics? Exchanges, control and capital markets in authoritarian capitalism. p. 12.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03085147.2020.1718913.

[44] Barry Naughton (2017). The regulatory storm: A surprising turn in financial policy.

https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/clm53bn.pdf.

[45] Franklin Allen, Jun Qian, Susan Shan, and Julie Zhu (2015). Explaining the Disconnection between China’s Economic Growth and Stock Market Performance. p. 3.

https://www.cicfconf.org/sites/default/files/paper_736.pdf.

[46] What Are the Policy Banks China Uses to Spur Economy? Bloomberg (2022).

https://archive.ph/DrsYd#selection-3453.0-3460.0.

Why does the West attack China’s Finance and Investment System?

[47] Middle Kingdom: Middle Income. Goldman Sachs (2022). p. 69.

https://www.gsam.com/content/dam/pwm/direct-links/us/en/PDF/isg_insight_middlekingdom.pdf?sa=n&rd=n

[48] John Ross (2015). The global significance of China’s discussion on the economy’s ‘supply side’.

https://archive.ph/z4Y65#selection-1785.19-1785.182.

[49] Dale Jorgenson (2005). Productivity, Vol. 3 Information Technology and the American Growth Resurgence. MIT Press. pp. 84, 305.

[50] Vu Minh Khuong (2013). The Dynamics of Economic Growth. pp. 196, 198.

[51] Dale Jorgenson (2009). The Economics of Productivity. p. VIII

[52] John Ross (2014). What the G20 needs to learn from China.

https://ablog.typepad.com/keytrendsinglobalisation/2014/11/what-the-g20-should-learn-from-china.html.

[53] John Ross (2016). Reality vs myth in US economic growth.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/reality-versus-myth-us-economic-growth-john-ross.

[54] Dale Jorgenson, Masahiro Kuroda, and Kazuyuki Motohashi (2007). Productivity in Asia: Economic Growth and Competitiveness. p. 128.

[55] Dale Jorgenson, Masahiro Kuroda, and Kazuyuki Motohashi (2007). Productivity in Asia: Economic Growth and Competitiveness. p. 176.

[56] Barbara Fraumeni, Dale Jorgenson, and Frank Gollop (1987). Productivity and US Economic Growth. p. 200.

[57] Charles Jones (2010). Intermediate Goods and Weak Links: A Theory of Economic Development. p. 2.

https://web.stanford.edu/~chadj/links500.pdf.

[58] Angus Madison (1991). Dynamic Forces in Capitalist Development: A Long-Run Comparative View. p. 40.