Corporate Governance in the People's Republic

How China governs enterprises and the truth about the "Social Credit" System

The way China engages in corporate governance and enterprise discipline has been subject to much scrutiny, particularly by the Left. Many in the Western Left claim that China’s corporate governance is far too lacking. This article is designed to go over the way China is able to exert its party influence over both state-owned and non-state-owned enterprises. It is the third part in our series of articles that conduct an in-depth investigation of China’s economy. Our first article of the series investigated the degree of state-control over China’s economy. The second article of the series investigated how finance, banks, and investments work in China, in addition to how China was able to survive the many financial crises mostly unharmed that many other countries - including the West - could not.

Corporate Social Credit

According to the Communist Party of China (CPC) document “The Planning Outline for the Establishment of a Social Credit System (2014 - 2020)”, the following is stated the establishment of a social credit system:

“... must have advancing the establishment of creditworthiness in government affairs, commerce, and society and establishment of judicial credibility as its primary content; must have advancing the establishment of a culture of creditworthiness and establishing mechanisms to encourage trustworthiness and punish untrustworthiness as key points; must be supported by advancing the establishment of industry and region specific credit, and developing credit services markets; must have raising the entire society’s awareness and levels of creditworthiness, and improving the economic and social operating environment as its goals; and must put people first, to form an environment across all society in which trustworthiness is honored and untrustworthiness is shameful, and make honesty and trustworthiness the entire populations’ conscientious behavioral norm.” [1]

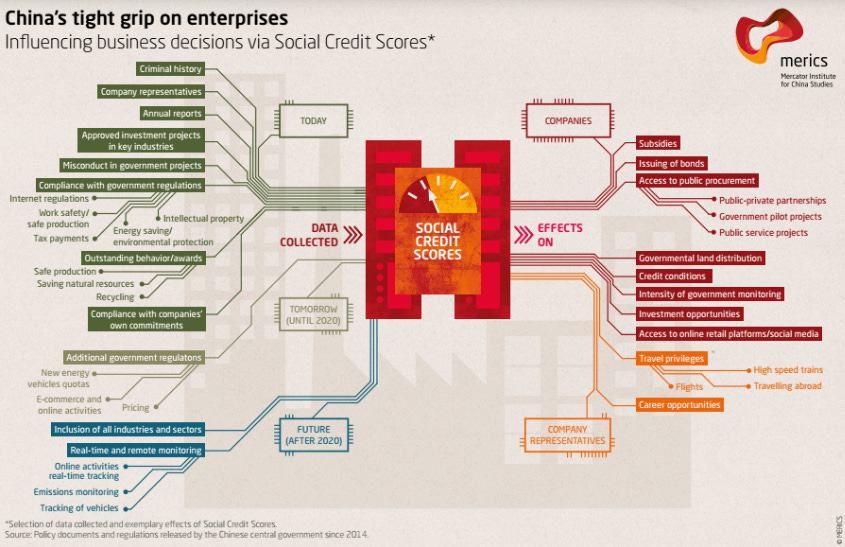

What is credit worthiness? It is being able to comply with financial agreements and willingness to pay debts. And in the context of the social credit score, to ensure companies enact on their promises. The score is used to regulate the private sector and continue to clamp down on potential exploitative behavior that may be undergone. In other words, social “credit” can also be translated from Chinese as social trustworthiness. The score is given to private firms and there are real punishments and drawbacks for those who do not comply or fail to achieve a high score.

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) is pushing ahead with social credit-based supervision of all commercial entities from large firms to small, independently owned and operated businesses, which prompted complaints over corporate privacy and heavy-handed government intervention [2]. The social credit rating will include court rulings, tax records, environmental protection issues, government licensing, product quality, work safety and administrative punishments by market regulators [2]. In 2019, Lian Weiliang, deputy chairman of the NDRC, stated the following:

“All the existing credit incentive and punishment measures listed in the memorandums are based on laws and regulations... For severe violations, especially those endangering life and property, harsh punishment will be adopted, such as a temporary or even permanent ban on market entry.” [2]

While the China Blacklisting system is still in its early stages, it is already the most prominent system of its kind worldwide. China has already put this system into action, and has barred thousands of Chinese residents’ rights to buy plane tickets and travel either domestically or abroad. However, most of the blacklisting that has occurred to date has been as a result of violations or misbehavior of companies and the individuals working for them. [3]

Individuals who end up on a blacklist due to mistreatment of workers or violating the laws around workers’ rights are given penalties. These penalties can be as severe as having their business license revoked or barring them from using social amenities and public services until they fix their social credit score. How the social credit score is measured according to CreditChina, the website responsible for openly publishing corporate social credit data lists the following reasons for a low social credit score:

Basic identifying information for the company, including the company’s Unified Social Credit Code and permits held;

Any applicable administrative penalties;

Any payment defaults recognized by the Courts;

Any instances of tax evasion and fraud;

Instances of illegal importing or exporting;

Unpaid wages

Ultimately, the Social Credit System is meant to serve as a market regulation mechanism. The goal is to establish a self-enforcing regulatory regime fueled by big data in which businesses exercise “self-restraint”. The basic idea is that with a functional credit system in place, companies will comply with government policies and regulations to avoid having their scores lowered by disgruntled employees, customers, or clients. Companies with bad credit scores will potentially face unfavorable conditions for new loans, higher tax rates, investment restrictions, and lower chances to participate in publicly funded projects. [4]

A study found that the Corporate Social Credit System could be used in a way that signals “corporate fealty” to the Party. This incentivizes more corporate social responsibility programmes such as participating in poverty alleviation, strictly implementing deadlines for national industrial and environmental policies. The credit system itself does not award scores based on profitability, profitability is not a metric that is factored. [5]

There is however a wide misconception that the social credit score is something that only impacts people. However, state owned enterprises and other government bureaucrats who work at state owned enterprises can be subject to the corporate social credit. The social credit system is ‘self-reflective’: Bureaucrats and politicians themselves will be subject to the regime, with the goal of reducing corruption. This core concept is known as “Government integrity” which is a part of Xi Jinping’s Anti Corruption crackdown. [3]

Blacklists and Redlists

As mentioned earlier, with the Social Credit System (SCS), there comes consequences to gaining low scores or high scores. This comes in the form of Blacklists and Redlists. The blacklist is negative while the redlist is positive.

A blacklist is a type of public record which identifies companies and individuals found in violation of a predetermined set of regulations — for example, one blacklist may identify companies which have violated work safety regulations, while another identifies parties found in violation of patent laws. A redlist is the opposite: a roster of companies and individuals demonstrating consistent compliance with a specific set of regulations, such as consistent tax payment or low rates of import-export violations. [6]

The majority of existing blacklists and redlists were created between 2016 and 2018. Since then, the announcement of new national-level lists has slowed dramatically. As of November 2019, forty established blacklists and eight redlists were in effect at the national level. Of these, about half have a broad scope, such as those targeting violations in the areas of environmental protection, import-export, social security, tax arrears, and e-commerce fraud. The remaining blacklists are only applicable to enterprises and professionals operating in specific sectors, such as financial services, transportation, insurance, salt production, domestic services, travel, real estate, food, agriculture, and medicine. [7]

Companies found to have engaged in “seriously untrustworthy behavior” may have their business license revoked and credit irreparable. And of course, being subject to imprisonment. [8]

These acts include:

Violations of food and drug safety, environmental protection, engineering quality, production safety, product quality, and fire safety regulations [8]

Bribes, tax evasion, debt default, failure to pay wages, illegal fund-raising, contract fraud, pyramid schemes, unlicensed operations, infringement of intellectual property rights, bid rigging, false advertising, infringement of consumer rights, infringement of investor rights, serious internet behavior violations, and disruption of social order [8]

An example of a company being subject to punishment from engaging in “seriously untrustworthy behavior” would be Shanghai Husi, the Chinese subsidiary of U.S. holding company OSI Group. In 2014, they were reported for using expired meat, falsifying production dates and violating hygiene regulations. These products had ended up in KFC and McDonalds in China. [9]

A court case found the firm guilty in 2016, after which the directly responsible employees within the company were sentenced to prison and fined for the crime of producing and selling fake and inferior products, as were members of Shanghai Husi’s holding company OSI. [10]

This had credit-related consequences: the local government revoked Shanghai Husi’s food production licenses, while the company was designated as a “seriously untrustworthy producer” and added to the food safety blacklist by Shanghai local government officials for a period of two years (2016-2018). Additionally, three key responsible parties (the quality supervisor, factory manager, and planning director) within the organization were personally blacklisted for a period of five years (2016-2021) [11]. The company reportedly lost RMB 6 billion in the year after the scandal, though how much of those losses resulted from Corporate Social Credit System (CSCS) penalties rather from the scandal more generally, is unknown [12].

The company did not repair their credit, and though OSI still operates in China, Shanghai Husi appears to have effectively halted operations. [13]

In Regard to Foreign Enterprises

Foreign enterprises are not free from the social credit score. Companies that do not comply or actively reject party building and the formation of party organizations within the enterprise (more on that later) will be penalized by the Social Credit System (SCS). A report published by the EU Chamber of Commerce estimates that multinational firms in China will be subject to approximately 30 different ratings under the Corporate SCS, the requirements of which will be dispersed across numerous government documents. Firms are also required to disclose to the Chinese government detailed data and other information about their operations and capabilities, which may include proprietary information or sensitive intellectual property. [14]

An example of which is that 44 airline companies attempting to operate in China were required to follow the Chinese mainland designation of Taiwan; failure to comply would result in their corporate social credit score being deducted. Japanese retailer Muji was fined over $30,000 for describing Taiwan as the “country of origin” on 119 clothing hangars last year. [15]

This further solidifies the state control over foreign enterprises inside China, where the terms are dictated by the state, and these corporations have to follow the line. When the Communist Party tells foreign entrepreneurs to jump, the response from these entrepreneurs is to ask how high and how far.

According to the EU Chamber of Commerce, the corporate social credit score system will mean life or death for foreign enterprises wanting to operate in China. China’s Corporate Social Credit System is here to stay. Businesses in China need to prepare for the consequences, to ensure that they live by the score, not die by the score. [16]

This further solidifies the fact that foreign enterprises cannot escape the grasp of the Communist Party of China.

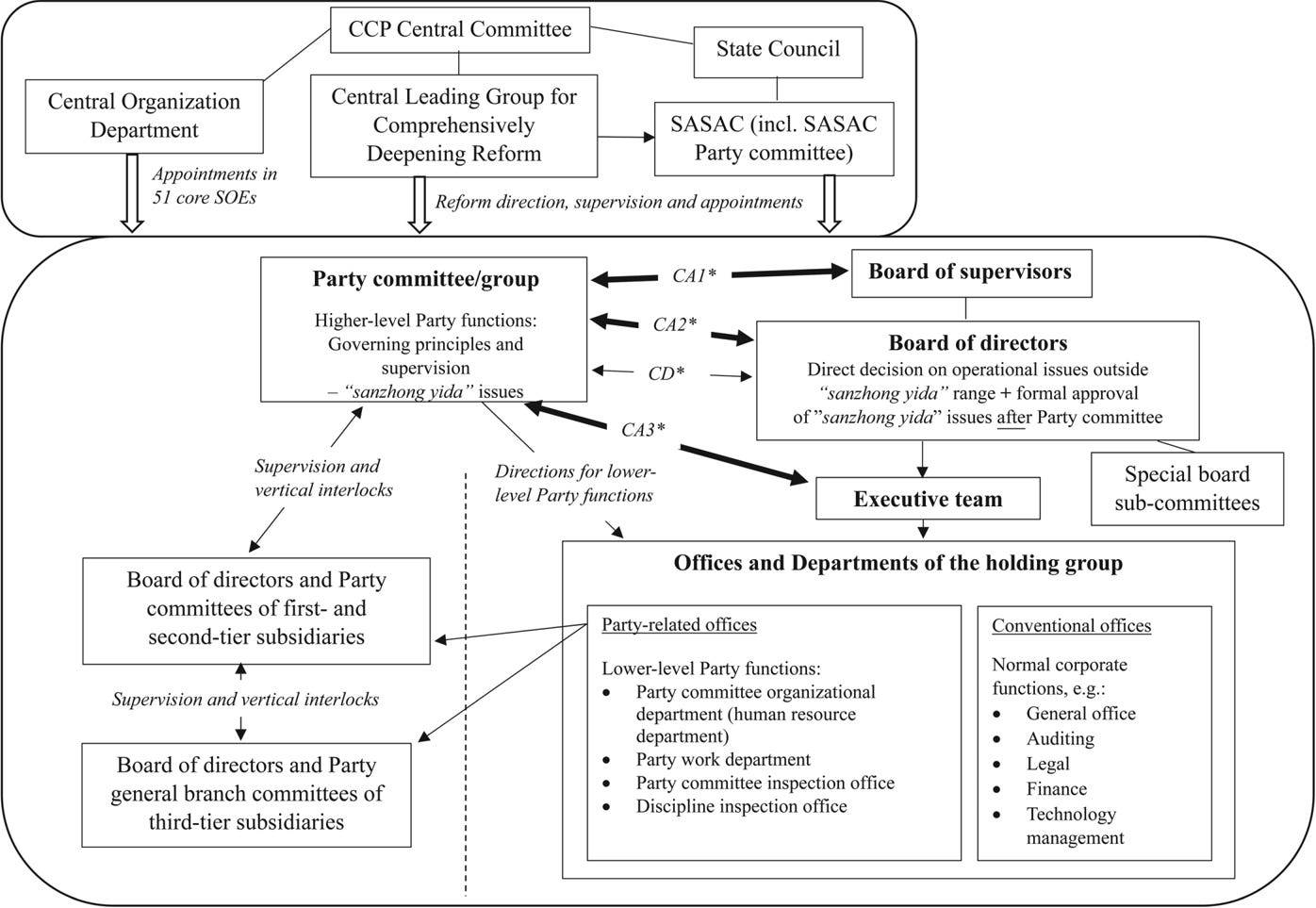

Corporate Party Organizations

A study in 2008 looking into listed organizations found that for every listed enterprises’ board of directors, there is a parallel power structure known as the firm’s Party Committee, headed by a party secretary. In the large SOEs (state-owned enterprises), the Party Secretary appoints the top executives and directors, often simply relaying orders from the Communist Party of China’s Central Organizational Department, and effectively exercising a leading role in the company. Thus, significant overlap between the Party committee or group with traditional corporate structures. Where the two structures do not overlap, real power flows through the party channels, leaving the board and formal corporate top executives with scant real authority. The figure below visualizes this arrangement. [17]

In the book, Capitalizing China, it was found that:

Parallel to this corporate governance system, each (Listed) enterprise also has a Communist Party Committee, headed by a Communist Party Secretary. These advise the CEO on critical decisions, and are kept informed by party cells throughout the enterprise that also monitor the implementation of party policies. Indeed, the party secretary plays a leading role in major decisions, and can overrule or bypass the CEO and board if necessary. For example, foreign independent directors on the board of CNOOC reportedly first learned of that enterprise's takeover bid for Unocal, an American oil company, from news broadcasts. Directors often also learn of such major strategic moves, and of equally major personnel moves such as the rotation of oil company top managers described earlier after the fact. Despite their formal powers, CEOs and boards are thought to welcome party advice, and any directors likely to have reservations are kept out of the loop to preserve harmony-especially if issues the CCP views as strategically important are involved. [18]

Furthermore, according to Article 33 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China:

Primary-level Party organizations in non-public sector entities shall implement the Party's principles and policies, guide and oversee their enterprises' observance of state laws and regulations, exercise leadership over trade unions, Communist Youth League organizations, and other people's group organizations, promote unity and cohesion among workers and office staff, safeguard the legitimate rights and interests of all parties, and promote the healthy development of their enterprises. [19]

Most of the listed shareholder firms have a party secretary. A study on 4,104 listed firms was conducted between 2000 and 2004, which represents 68% of the total firms with A-shares in China during that period. Note, referring back to our previous article, A-Shares are shares of companies based in mainland China that are listed on either the Shanghai or Shenzhen stock exchanges that are off limits to foreigners. It was found in this study that only 11% of the firms said that they did not have a party secretary. In those firms with party secretaries, many of the secretaries hold other management positions as well: 5% also serve as both the chairman and the CEO; 18% also serve as the chairman; 6% also serve as the CEO; and 26% also serve as a supervisor, director, or executive. Thus, many party secretaries have a significant effect on firm management. [20]

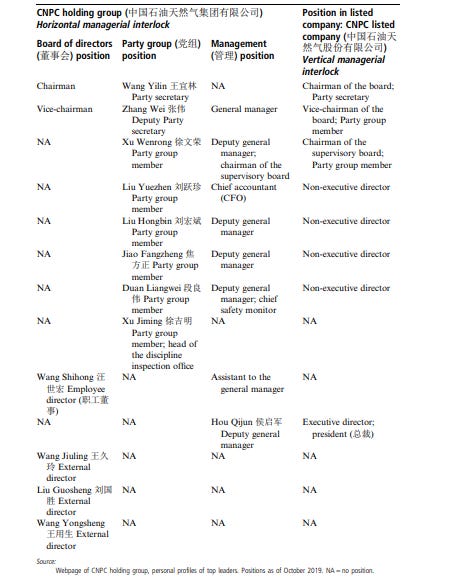

One example can be observed with the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), a central SOE holding group. As of October 2019, the Party group in CNPC had eight members (see Table below), six of whom simultaneously held top management positions: the chairman of the board, the general manager, the chairman of the supervisory board, the head of the discipline inspection office, the chief accountant (i.e. chief financial officer) and the chief safety monitor. With this level of insider control, the Party group dominates corporate decision making. In addition, many of these Party group members simultaneously held positions in the publicly listed subsidiary company – as board members and/or members of the subsidiary Party organization. For example, Liu Yuezhen was simultaneously a Party group member, chief accountant of the parent company and non-executive director of the subsidiary. Thus, to recap, the Party committee exercises strong horizontal control within the parent company’s top management through overlapping positions, but also exercises strong vertical control through SOE control of subsidiary enterprises and more overlapping positions. The result is more streamlined management as a result of how embedded the Party is in these enterprises. [38]

In Taizhou, 39 listed firms in 2018 modified their charter to include party construction in their constitution. And the party organization’s role entails the party branch to have more say in the company's selection and employment of personnel, to play a core role in political leadership, as well as decision-making in other major corporate decisions. For instance, feedback/voice on the acquisition of other enterprises, which falls under having a role in corporate business decisions. [21]

Interestingly, as a side effect of having Party Committees, a study found that Communist Party Committees actually improved enterprise value and reduced corruption within SOEs, indicating that they are not just a tool to enforce party leadership, but also assist positively in business decisions. [22]

Another study found that while ostensibly cooperative enterprises (Township Village Enterprises) had private revenue rights, their control rights were not. In reality, collective enterprises are under close control of the government. Major investment and employment decisions could not be made without government direction or approval. [23]

Enterprises which have party committees are much more likely to engage in “Green Innovation”, which refers specifically to inventing technologies or having processes which reduce environmental pollution. [24]

The Three Importants and One Big

But what does this entail specifically? How do party committees actually engage in their day-to-day management of enterprises? One of the largest key aspects of this is the ability to set performance indicators. The party’s pre-decision powers include the “three importants and one big” (sanzhong yida, 三重一大), which refers to:

Major strategic decisions concerning the “important issues” i.e. implementation of party-state principles, policies, laws and regulations, and matters related to security and stability, in addition to enterprise development strategy;

Appointments and dismissals of “important cadres” of mid-level or above in the enterprise holding group and in directly subordinate enterprises and units;

Major project arrangements for “important projects” that have an impact on the scale of assets, capital structure, profitability, production equipment and technical conditions;

The “one big” (yida, 一大), which refers to large-scale capital operations, meaning the use of large amounts of funds. [25, 38]

This doesn’t occur just in SOEs but also in mixed ownership enterprises (more on that later) where the state holds a significant minority stake. [26]

First and foremost, party committees (party groups) at all levels are expected to actively reform and improve leadership methods, adhere to and improve democratic centralism, combine collective leadership with individual division of labor and responsibility, fully develop intra-party democracy, and strive to improve scientific decision-making, democratic decision-making, and decision-making in accordance with the law, ability and level. Moreover, party group members, especially the principals in charge, should correctly handle the relationship between democracy and centralism, work together with decision-making bodies, take the lead in implementing democratic centralism, ensure the correct exercise of power, and prevent the abuse of power. [27]

Intra-Party regulations shall be decided by the shareholders' meeting, the board of directors, the management team without a board of directors, the workers' congress/union and the party committee (party group) matters. It mainly includes the major measures taken by enterprises to implement the party and the country's lines, principles, policies, laws and regulations, and important decisions of superiors, enterprise development strategies, bankruptcy, restructuring, mergers and reorganizations, asset adjustments, property rights transfers, foreign investments, interest allocation, organizational adjustments, etc. major decisions on corporate party building, security and stability, and other major decision-making matters. [28]

Party Organizations in Foreign Enterprises

Foreign enterprises and their joint-ventures are not free from party organizations. As the majority of foreign enterprises are actually joint-ventures ran with SOEs (State-owned enterprises), naturally there would be a spillover in terms of party committees. Party committees were first implemented in SOEs afterall and naturally their subsidiaries (which include joint-ventures with foreign companies) would be affected as a result.

In 2018 an analysis prepared by the European Commission investigating the Chinese Party-State’s role in the domestic Chinese economy. It noted that Party organizations in both SOEs and private companies “can potentially wield significant influence, and allow for the CCP to directly influence the business decisions of individual companies.” [29]

In May 2018, the US-China Business Council noted that certain SOE joint venture companies had asked some of their foreign partners to alter their articles of association to support Party groups within the joint venture, even going so far as to request that they be amended to allow critical matters to be approved by the party organization before they are presented to the board. [29]

In one example, Mercedes-Benz established a Party organization in its local Chinese joint venture in 2013. The secretary of the Party organization participates in the company’s economic management meetings through the entire process and has full authority to participate in the company’s major decision making. This means that even in joint-ventures, party organizations still have sway in major decision making and economic management. [30]

In 2018, a Samsung subsidiary had seven Chinese executives of the company who are all Party members and 74 percent of middle managers and above are Party members. The same article notes that 70.8% of all foreign enterprises have party organizations. In Pinpu Company given in the article, it was found that Party organizations play decisive roles in R&D decisions as well as decisions over production optimization. They also play a role of promoting party policies, such as for instance with Ford’s China subsidiary being convinced to start investing in New Energy Vehicles. In Nokia Shanghai, it was found that party organizations assisted heavily in human resources, especially in regard to employee management and development plans. [31]

Another 2018 article on Nissan’s automotive joint venture Dongfeng Motor Co. notes that their Party organization has been written into the enterprise charter, with members of the Party organization playing a role in enterprise decisions. This includes ensuring the direction of business development, complying with national laws and regulations, ensuring legal operations, safeguarding the legitimate rights and interests of employees, and promoting corporate stability, especially in the selection and use of talents. [32]

Control Via Shares

Previous essays in the series have gone over how limited liability corporations (Multiple shareholders in one company) could be controlled/steered towards state directives via internal corporate governance through the use of a majority or controlling state shareholder that coordinates the enterprise alongside party directives.

As mentioned earlier, it is not just SOEs that have implemented the Party Committees, but also limited liability corporations, some of which are listed on the stock market while others have a significant minority state share.

Corporate groups in the People’s Republic of China, and by extension their subsidiaries and divisions, are therefore actually controlled by Party-State nomenklatura insider appointees working at the core holding company level, and as directors and officers of the subsidiary entities controlled by the core holding company. As Party-State bureaucratic political actors seeking advancement in the Party system, these individuals are perfectly responsive to Party-State policy (which necessarily includes national industrial policy), while at the same time they are content to ignore the interests of external minority shareholders in the listed subsidiaries they formally manage. [33]

Consequently, there are also ways for the CPC to institute corporate governance within these mixed ownership enterprises without establishing a controlling/majority share in these companies, via something that is known as a golden share. A golden share is a type of share that gives its shareholder veto power over changes to the company's charter. One golden share controls at least 51% of voting rights and may be issued by private companies or government enterprises. [34]

This concept was first introduced in 2013, to allow the CPC to exert more influence over private enterprises, particularly media conglomerates [35]. Between 2018 and 2022, several government entities took 1% stakes in popular news and content platforms, including US-listed Sina Weibo, 36kr, Qutoutiao and Kuaishou, according to company filings or public registration records. [36]

The stakes in subsidiaries of Alibaba and TikTok parent ByteDance Ltd. have allowed the government to get in on—and police—the growth of the tech behemoths. Golden shares have become a useful tool to keep companies like these in line with party objectives without the need for the state being a major stakeholder. Companies that sell the government the much smaller stakes called golden shares are finding that even this way, the government is getting a lot of power over their businesses. The director whom China’s cybersecurity watchdog named to the board of ByteDance’s main subsidiary has veto rights over content on apps including Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, according to people close to the subsidiary. The director also can vote on corporate issues such as the subsidiary’s personnel decisions, compensation packages and investment or divestiture plans. [37]

Conclusion

In short, the idea that corporate entities, whether foreign, private or collective are somehow free from state influence, but more specifically party influence is untrue. Even companies with minority shares from the State have party committees onboard, let alone joint ventures with foreign enterprises. The Social Credit System is a means to hold corporations and their bosses accountable to certain standards to the benefit of the mass public. Corporate Governance in China is one that does not allow any corporate entities, SOE or non-SOE, to escape its grasp.

Bibliography

[1] State Council Notice concerning Issuance of the Planning Outline for the Establishment of a Social Credit System (2014-2020)

https://archive.ph/Z0H0W#selection-851.0-851.124.

[2] Frank Tang (2019), China pushing ahead with controversial corporate social credit rating system for 33 million firms, South China Morning Post.

https://archive.ph/sqFN6#selection-803.13-803.110

[3] Drew Donnelly (2024), China Social Credit System Explained – What is it & How Does it Work?

https://nhglobalpartners.com/china-social-credit-system-explained/#:~:text=The%20China%20social%20credit%20system%20is%20a%20broad%20regulatory%20framework,and%20governmental%20entities%20across%20China.

[4] Mirjam Meissner (2017), China's Social Credit System: A big-data enabled approach to market regulation with broad implications for doing business in China.

https://www.chinafile.com/library/reports/chinas-social-credit-system-big-data-enabled-approach-market-regulation-broad.

[5] Lauren Yu-Hsin Lin and Curtis J. Milhaupt (2023), China’s Corporate Social Credit System: The Dawn of Surveillance State Capitalism.

https://journals.scholarsportal.info/pdf/03057410/v256inone/835_ccscstdossc.xml_en.

[6] Kendra Schaefer (2020), China’s Corporate Social Credit System. p. 26.

https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Chinas_Corporate_Social_Credit_System.pdf.

[7] Kendra Schaefer (2020), China’s Corporate Social Credit System. p. 26-27.

https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Chinas_Corporate_Social_Credit_System.pdf.

[8] Kendra Schaefer (2020), China’s Corporate Social Credit System. p. 31.

https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Chinas_Corporate_Social_Credit_System.pdf.

[9] Geoffery Smith (2014), OSI axes Shanghai firm that sold tainted food to KFC, McDonald’s.

https://fortune.com/2014/09/22/osi-axes-shanghai-firm-that-sold-tainted-food-to-kfc-mcdonalds.

[10] Zhang Danyang (2017), Announcement Regarding the Key Supervision List of Serious Violator among Food and Drug Manufacturers and Related Responsible Persons (No. 2017004).

https://web.archive.org/web/20230112141753/http://www.spaq.sh.cn/renda/n36574/n36754/n36755/u1ai6245860.html

[11] Wu Chunwei (2016), Hufuxi Foods Produces Fake and Shoddy Products and is Included in the Illegal and Dishonest Enterprise Blacklist.

https://web.archive.org/web/20161005122952/http://sh.eastday.com/m/20161004/u1a9784299.html.

[12] The Second Anniversary of Shanghai Fuxi’s Expired Meat Incident, Caixin (2014).

http://special.caixin.com/event_0720_1/.

[13] “OSI Investment Group”

[14] China's Corporate Social Credit System, Congressional Research Service (2020). p. 2.

https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11342.

[15] Tara Francis Chan (2018), It looks like China is extending its Black Mirror-like 'social credit system' to overseas companies.

https://www.businessinsider.com/china-social-credit-system-controlling-foreign-companies-2018-6.

[16] EUROPEAN CHAMBER REPORT ON CHINA’S CORPORATE SOCIAL CREDIT SYSTEM A WAKE-UP CALL FOR EUROPEAN BUSINESS IN CHINA, European Chamber (2019).

https://www.europeanchamber.com.cn/en/press-releases/3045/european_chamber_report_on_china_s_corporate_social_credit_system_a_wake_up_call_for_european_business_in_china.

[17] Randall Morck, Bernard Yeung, and Minyuan Zhao (2008), Perspectives on China's outward foreign direct investment.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5223340_Perspectives_on_China's_outward_foreign_direct_investment.

[18] Randall Morck, Bernard Yeung, and Minyuan Zhao (2012), Capitalizing China, p. 8.

https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c12067/c12067.pdf.

[19] Article 33 - Constitution of the People’s Republic of China

[20] Wei Yu (2013), Party Control in China’s Listed Firms. p. 6.

https://ideas.repec.org/a/fau/fauart/v63y2013i4p382-397.html.

[21] Ding Shan and Xu Ziyuan (2018), 39 listed companies in Taizhou, Zhejiang have “Party building in their constitution.

http://dangjian.people.com.cn/n1/2018/0810/c117092-30221892.html.

[22] Shengbin Wang, Jiafeng Zheng, and Yongqian Tu (2023), The Communist Party of China embedded in corporate governance and enterprise value: Evidence from state-owned enterprises.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1544612323001393.

[23] Nicholas Hope, Dennis Yang, and Mu Li (2003). How Far Across the Rivers? Chinese Policy Reform at the Millennium. p. 99.

[24] Yun Gu, Zhaohui Yang (2023). The more red the greener? How the Communist Party of China's party organizations influences corporate green innovation.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1544612323002325.

[25] Opinions on promoting state-owned enterprises to implement the "three important and one" decision-making system, Xinhua News Agency (2010).

https://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2010-07/15/content_1655395.htm.

[26] Barry Naughton and Briana Boland (2023), CCP Inc. The Reshaping of China’s State Capitalist System, Center for Stategic and International Studies. p. 15.

https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2023-01/230131_Naughton_Reshaping_CCPInc_0.pdf?VersionId=pJl3iB.DqMILjtq_qMx.8eN5IvUOHg.Y.

[27] Mengcheng Prosecutor’s Office (2023), What is the "Three Importants and One Big” System?

https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/650227858

[28] Opinions on promoting state-owned enterprises to implement the "three important and one" decision-making system, Xinhua News Agency (2010).

https://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2010-07/15/content_1655395.htm.

[29] Scott Livingston (2021), The New Challenge of Communist Corporate Governance, Center for Strategic and International Studies. p. 3.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep28759?seq=3.

[30] Lu Ning (2015), Lu Ning: Transnational giants begin to identify with China’s “party culture”, Guancha.

https://www.guancha.cn/LuNing/2015_04_24_317099.shtml?web.

[31] Ye Xiaonan and Guo Chaokai (2018), “Party Building + Foreign Enterprises” Releases “Red Productivity”.

http://dangjian.people.com.cn/n1/2018/0118/c117092-29772309.html.

[32] Dongfeng Co Ltd (2018), Party building leads the way and creates a new realm of development. A review of the party building work of Dongfeng Co., Ltd.

https://www.dfl.com.cn/sp/html/party/partyNewsDetail48-zh.html.

[33] Nicholas Howson (2017), China 's 'Corporatization without Privatization' and the Late 19th Century Roots of a Stubborn Path Dependency. p. 11

https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3021&context=articles.

[34] Rajeev Dhir (2022), Golden Share: Overview, Benefits and Examples.

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/g/goldenshare.asp.

[35] The Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Several Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reform, Xinhua News Agency (2013).

https://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2013-11/15/content_2528179.htm.

[36] Laura He (2023), China still wants to control Big Tech. It’s just pulling different strings, CNN.

https://www.cnn.com/2023/01/27/tech/china-golden-shares-tech-regulatory-control-intl-hnk/index.html.

[37] Lingling Wei (2023), China’s New Way to Control Its Biggest Companies: Golden Shares, Wall Street Journal.

https://archive.ph/CFbLo.

[38] Kasper Ingeman Beck and Kjeld Erik Brødsgaard (2022). Corporate Governance with Chinese Characteristics: Party Organization in State-owned Enterprises.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/china-quarterly/article/abs/corporate-governance-with-chinese-characteristics-party-organization-in-stateowned-enterprises/ECA0C9226DDEA3F13B4AA5CD7D83AB35.