The History and Theory behind the Federal Reserve

A dive into the understudied and uncovered...

Written by: Alcazar

INTRODUCTION

Central banking and monetary theory have long been a blind spot for Marxists. When libertarians argue that established financial power originates from a malicious expansion of state power, or when anti-Semites claim that it is all due to the Jews, one can obviously counter that finance capital is, in fact, responsible. However, without concrete analysis, "finance capital" is merely another phrase, another bogeyman behind the curtain, and the connection between Marxist theory and the historical development of central banking remains unclear. Without concrete analysis, we achieve no more than the ideological mystification of those who blame all social ills on the state or on Jewish people. Unlike our enemies, however, we are not bluffing.

The genealogy of modern central banking is a matter of historical record, a record that the theories of Marx, Engels, and Lenin elucidate rather than mystify. In short, the record shows that established finance developed a method for issuing emergency liquidity—thereby protecting themselves from periodic crises in the money market—independently of the state. The odious bailout function of central banks merely institutionalized and scaled up the role that private actors like the New York Clearing House and J.P. Morgan Sr. played in mitigating earlier crises. Moreover, it was this precise network of institutions and men (in a word, finance capital) that was responsible for the creation of the Federal Reserve. None of this is mysterious from the perspective of Marxist-Leninist theory.

Theory

Marx deduced the possibility of a general crisis from the asymmetry inherent in the process of capital expansion itself. Specifically, he identified the possibility that "the supply of all commodities can be greater than the demand for all commodities, since the demand for the general commodity, money, or exchange-value, is greater than the demand for all particular commodities." [1]

During crises, money becomes scarce, ruining those who get caught holding the bag (of commodities). Underlying this is the necessity that value, in order to expand, must continuously transform itself between use value and exchange value, and that only in the transition from commodity to money can surplus value emerge. In the M-C-M' cycle, C-M' is the critical junction, and the recurring problem is that C cannot become M' without the ruination of countless capitalists.

In so far as the payments balance one another, money functions only ideally as money of account, as a measure of value. In so far as actual payments have to be made, money does not serve as a circulating medium, as a mere transient agent in the interchange of products, but as the individual incarnation of social labour, as the independent form of existence of exchange-value, as the universal commodity. This contradiction comes to a head in those phases of industrial and commercial crises which are known as monetary crises. Such a crisis occurs only where the ever-lengthening chain of payments, and an artificial system of settling them, has been fully developed. Whenever there is a general and extensive disturbance of this mechanism, no matter what its cause, money becomes suddenly and immediately transformed, from its merely ideal shape of money of account, into hard cash. Profane commodities can no longer replace it. The use-value of commodities becomes valueless, and their value vanishes in the presence of its own independent form. On the eve of the crisis, the bourgeois, with the self-sufficiency that springs from intoxicating prosperity, declares money to be a vain imagination. Commodities alone are money. But now the cry is everywhere: money alone is a commodity! As the hart pants after fresh water, so pants his soul after money, the only wealth. In a crisis, the antithesis between commodities and their value-form, money, becomes heightened into an absolute contradiction. Hence, in such events, the form under which money appears is of no importance. The money famine continues, whether payments have to be made in gold or in credit money such as bank-notes. [2]

This spirals into a general crisis due to the chain of "mutual claims and obligations, the sales and purchases," which is the connective tissue of commodity circulation in the capitalist economy. Once a crisis begins, it spreads with virulence.

The flax-grower has drawn on the spinner, the machine manufacturer on the weaver and the spinner. The spinner cannot pay because the weaver cannot pay, neither of them pay the machine manufacturer, and the latter does not pay the iron, timber or coal supplier. And all of these in turn, as they cannot realise the value of their commodities, cannot replace that portion of value which is to replace their constant capital. Thus the general crisis comes into being. This is nothing other than the possibility of crisis described when dealing with money as a means of payment; but here—in capitalist production—we can already see the connection between the mutual claims and obligations, the sales and purchases, through which the possibility can develop into actuality. [1]

Because the reconversion into M' is the sine qua non for capitalist production, the entire operation comes to a grinding halt. Modern bourgeois economists refer to this as the “survival constraint.” As Engels writes in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific...

The necessity of this transformation into capital of the means of production and subsistence stands like a ghost between these and the workers. It alone prevents the coming together of the material and personal levers of production; it alone forbids the means of production to function, the workers to work and live. On the one hand, therefore, the capitalistic mode of production stands convicted of its own incapacity to further direct these productive forces.

A variable money supply allows for artificial liquidity infusions that temporarily circumvent the breakdown of payments described above. During a crisis, no one is willing to part with money to buy commodities that need to circulate, causing the entire cycle to break down. Under an elastic currency regime, such a crisis is met with infusions of artificial liquidity. This acts as a sort of cardiopulmonary resuscitation for the economic body—when blood stops flowing, outside pressure can get it going again.

But how to address this? Marx is clear that, because it permeates the process of circulation, credit can bridge the payment gap. However, in times of crisis, credit evaporates. The demand for hard currency extinguishes credit as fearful bankers call in their loans. Even when long-term solvency is assured, it does nothing to alleviate the immediate crisis. Everyone knows a crisis is a temporary situation, that credit and easy money will soon return—but in a state of competition, where it is clear someone will be left crushed between an unwilling market and the chain of "mutual claims and obligations," the immediate impulse of every capitalist is self-preservation, leading to the hoarding of liquidity. No one will lend, and no one will buy. It is this crisis that creates the fear, and the fear that fuels the crisis.

The fear is universal, but it is not equally distributed. The largest, most well-connected banks are in the best position, and by banding together, they are able to jointly issue emergency liquidity. In doing so, they temporarily suspend the conditions of capitalist competition. Like a cartel, capitalists annul their character as capitalists, cooperating to preserve their dominant position in the market. In Volume III of Capital, Marx describes the tendency toward financial organization and cooperation as “the abolition of the capitalist mode of production within the capitalist mode of production itself,” and declares it to be the “phase of transition to a new form of production.” As crises recur, each time on a greater scale, this rebellion of the productive forces against their nature as capital "forces the capitalist class itself to treat them more and more as social productive forces," as Engels writes…

In the trusts, freedom of competition changes into its very opposite — into monopoly; and the production without any definite plan of capitalistic society capitulates to the production upon a definite plan of the invading socialistic society. [5]

And Marx…

When we pass from joint-stock companies to trusts which assume control over, and monopolize, whole industries, it is not only private production that ceases, but also planlessness. [6]

Marx and Engels are describing joint-stock companies and trusts, which, in their day, were the avant-garde of capitalist combination. These were the direct precursors of the industrial combines and monopolies described by Lenin in Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. By the early 20th century, Lenin observed that a similar process of cooperative interlocking was occurring among the great banks. These banks, through their ability to “ascertain exactly the position of the various capitalists, then control them, influence them by restricting or enlarging, facilitating or hindering their credits,” wielded decisive influence over industrial and merchant capital. For this reason, Lenin describes imperialism as the “ascendancy of finance capital.” [7]

Just as Marx saw joint-stock companies and Engels saw trusts as evidence of an “invading socialistic society,” Lenin described finance capital and imperialism, along with their relationship with the state, as “the transition from the capitalist system to a higher social economic order.” For Marx, Engels, and Lenin, socialism was not a voluntaristic, self-conscious project undertaken by individuals subjectively opposed to capitalism. Rather, socialism was the inevitable conclusion of the objective contradictions essential to the very process of capitalist reproduction. The circulation of commodities at exchange value would lead to a falling rate of profit and economic crises, which would trigger the consolidation of capital under fewer and fewer firms. At some point, this process would no longer be sustainable as a free system without intervention. Socialism is, therefore, the sublation of capitalism in the precise Hegelian sense: in preservation (cartels setting prices, central banks ordering the economy), it passes away (competition ceases, property becomes hereditary and institutional). It is this insight into the process that distinguishes scientific from utopian socialism.

Engels writes that "the official representative of capitalist society—the state—will ultimately have to undertake the direction of production." Writing in 1880, Engels imagined this as "conversion into State property," but what if this 'direction of production' need not be so direct? Lenin described how cartelization culminated in a system with powerful banks at its apex. It is here, in this indirect and abstract sphere, that states intervene in the form of central banks managing the money supply. Finance capital, out of necessity, began to treat the money market as “social productive forces," cooperating to mitigate periodic crises—and when private bailouts no longer sufficed, they turned to the state.

Before the Federal Reserve: the National Bank System and the New York Clearing House

Since 1863, America had operated under the National Bank System, a veritable relic. Ostensible decentralization left banks across the country at the mercy of New York. Created by Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase in the midst of the Civil War, banks participating in the system were required to invest in a proportionate amount of government bonds, deposited with the Treasury as collateral, in order to issue notes. Similar to the conditions surrounding the creation of the Bank of England, Chase aimed to force banks to invest in government debt to finance the war. In that desperate context, the system worked well enough for that specific purpose. But half a century later, it had become an unwieldy and inflexible giant. Currency was inelastic, as it could only expand through investment in government bonds, bearing no relation to the level of trade. Strict reserve requirements kept 25% of New York deposits locked away, and similar restrictions on other banks kept reserves largely immobile. At the top, there was nothing, as member banks acted in their own interest. In times of crisis, currency remained inelastic, strict requirements kept existing reserves immobile, and there was no central authority to coordinate the system’s response.

De jure, the system was acephalic and had no recourse to elastic currency. De facto, things were complicated by the presence of the New York Clearing House. By 1860, the “largest ten banks in New York City [held] 46% of the total banking assets of the City.” This ongoing concentration of capital was reflected in the explicit organization of New York banking during the 1850s in the form of the New York Clearing House Association, formed in 1853. Originally organized to facilitate specie transfer, the Clearing House “soon developed into a mutual association capable of coordinating and enforcing cooperative action among the city banks … controlled by a committee composed of five bank officers, usually representing each of the most powerful banks in the city… regulating the admission or expulsion of Clearing House members.” [9]

By 1907, the organization functioned as an unofficial 'bankers' bank' in this vacuum. It managed the daily exchange of checks between banks and, more importantly, pooled member bank reserves to issue emergency currency ('loan certificates') to mitigate fallout during crises. [10] Holding this power, it could dictate terms to the lesser banks during crises. To deny their services at such a juncture was to destroy, and they knew this. With this power, the clearinghouse, "dominated by the more conservative and solidly entrenched institutions which were either within the Morgan sphere of influence or the National City Bank [Rockefeller] sphere of influence," imposed an order on New York finance that favored establishment finance. [11]

Necessity: the 1907 Crisis

Despite the grumblings of certain bankers, the question of currency and banking reform could be ignored as long as economic conditions allowed. After the 1907 crisis, bankers as a class could no longer ignore it. As is often the case, the crash followed a period of feverish speculation. By the fall of 1906, this boom was beginning to drain English gold across the Atlantic, and the Bank of England took notice. As Frank Vanderlip reported to James Stillman, “The Bank of England is extremely nervous on the subject of gold exports.”[12] Later that fall, the Bank of England took decisive action.

London raised its interest rate from 3.5 percent to 6 percent. The Reichsbank in Berlin raised rates as well. Since international capital ever flows to where the yield is highest, these moves inevitably induced investors to ship their gold back across the Atlantic. The Bank of England further insulated the mother country from the overheated American economy by directing British banks to liquidate the finance bills—short-term loans—that they provided to American firms, thereby tightening credit. [13]

When the Mercantile National Bank, along with a number of failing trusts, appealed to the Clearing House for aid, the Clearing House demanded the "immediate resignation of Messrs. Heinze, Morse, and Thomas from all their banking connections." [14] For days on end the newspapers blared the casualties of the Clearing House sterilization campaign. As the spectacle grew, the public began to balk, and a run began on banks and banking trusts. Already, the American economy was headed toward crisis. More immediately, the crisis was caused by the failure of a bid to corner the copper market by F. Augustus Heinze of the United Copper Company in collaboration with his brother Otto and the notorious Charles W. Morse. Over mid-October an attempt was made to squeeze short sellers, but the attempt failed. Heinze and company were ruined.

The damage caused by these failures would probably have been limited had Heinze and his associates not been both bankers and gamblers. Heinze was president of the Mercantile National Bank, and Morse and Thomas were directors of it. Naturally, depositors became suspicious and began to withdraw their funds. Suspicion also spread to the Morse chain of banks. As the Mercantile experienced a drain on its cash from uneasy depositors, it sought help from the New York Clearing House.[15]

Due to the extreme degree of interlocking among the boards of these banks and trusts, the crisis was particularly virulent. Morse was associated with Charles T. Barney of the Knickerbocker Trust Company, who occasionally lent him money. One of the largest banks in New York, Knickerbocker Trust was targeted by the Clearing House, which demanded resignations. This, combined with the National Bank of Commerce's refusal to clear their checks, spelled disaster for the trust. On October 21st, executives met in a popular restaurant to discuss the emergency. They resolved that only J.P. Morgan could save them and called on him early the following morning.

Morgan the Fixer

Morgan had a reputation for fixing these kinds of problems. Back in 1893, he had all but single-handedly diffused a similar crisis. In 1890, when the Barings bubble collapsed in Argentina, British capital fled the New World, spurred by fears that the U.S. government would begin experimenting with bimetallic currency.[16] In 1893, with U.S. gold reserves evaporating, Grover Cleveland approached John Pierpont Morgan Sr. and August Belmont Jr., the American representative of the London Rothschilds.[17] They offered him $50 million at 3.75%, an outrageous rate that Cleveland declined. On the night of February 7th, Morgan and his coterie arrived at the White House. Informed that they could not simply drop in on the President of the United States, Morgan replied, “I have come down to see the president, and I am going to stay here until I see him,” and there he waited, playing solitaire through the night.[18] In the morning, they were received, and Cleveland told them that a public issue of bonds, as opposed to their private scheme, had been decided upon. Morgan declared this impossible, and Cleveland asked for his alternative.

Pierpont laid out an audacious scheme. The Morgan and Rothschild houses in New York and London would gather 3.5 million ounces of gold, at least half from Europe, in exchange for about $65 million worth of thirty-year gold bonds. He also promised that gold obtained by the government wouldn’t flow out again. This was the showstopper that mystified the financial world—a promise to rig, temporarily, the gold market. When the syndicate bonds were offered, on February 20, 1895, they sold out in two hours in London and in only twenty-two minutes in New York. [19]

So, in 1907, when the sky was falling on top of New York finance, Morgan seemed the man to call. He formed a team of young bankers loyal to him, including Henry P. Davison of First National Bank and Benjamin Strong of Morgan's own Bankers Trust. He sent these men to audit Knickerbocker's books and found them wanting. Knickerbocker was allowed to fail on October 22.[20]

At this point, even Morgan felt himself out of his depth and sought government assistance. Back in September, with the crisis all but inevitable, Morgan had appealed directly to Theodore Roosevelt. At that time, the Treasury had shifted millions of dollars to commercial bank deposits around the nation and tried to limit government withdrawals. Now, on October 23, Morgan and other bankers met at a Manhattan hotel with Treasury Secretary George B. Cortel, and the following day Cortel put $25 million in government funds at Pierpont’s disposal.[21] Through the rest of October and into November, Morgan effected a series of last-minute miracles, saving the New York Stock Exchange, a number of trusts, and New York City itself. By November, the Treasury was again intervening, issuing "$150 million in low-interest bonds and certificates and permitting the banks to use government securities as collateral for creating new currency — an expedient device for pumping up the money supply in a hurry."[22] Effectively, the alliance between Morgan and the U.S. Treasury was attempting to act as a central bank by providing emergency liquidity.

In all, the devastation was palpable. New York's trusts had lost 48% of their deposits.[23] The stock market plunged 40%, and steel production was severely reduced.[24] In the wake of such a crisis, it was readily apparent that something had to be done. A decade earlier, Morgan and his syndicate had defused the 1893 crisis with relative ease, but in 1907, Morgan needed the backing of the U.S. Treasury, and even then, it was a close call. The age of paternalistic Morgan bailouts had come to an end, and Morgan himself was growing old. After the panic subsided, Senator Nelson W. Aldrich declared, “Something has got to be done. We may not always have Pierpont Morgan with us to meet a banking crisis.”[25]

Jekyll Island and the push for the Federal Reserve

To this end, the National Monetary Convention was established by the Aldrich–Vreeland Act of May 8, 1908. Chaired by Nelson Aldrich, the Republican whip and most powerful senator at that time, the work was mainly carried out by him and economist A. Piatt Andrew, assistant to the commission.[26] They were to tour Europe, studying central banking practices there, and report back with a plan for banking reform for the United States. Morgan was intimately involved. During the lead-up to the commission's departure, he received a coded cable stating that Henry P. Davison would advise Aldrich: “It is understood that Davison is to represent our views and will be particularly close to Senator Aldrich.”[27] Before the commission left for Europe, Davison went ahead to England to meet with Morgan, who requested a private central bank akin to the English model.[28]

The National Monetary Commission returned from Europe in the fall of 1908, and the product of their work, 23 volumes of studies and interviews, began to appear in the fall of 1910. In November of that year, a secret meeting attended by representatives of the great financial houses was hammering out, in substance, the function and structure of the Federal Reserve. Already with the National Monetary Convention, men like Aldrich were aware of the uproar muckrakers could make with the frank reality that a small circle of political and financial elites were planning to unilaterally remake U.S. banking. Aldrich had written privately, upon forming the Convention, that "My idea is, of course, that everything shall be done in the most quiet manner possible, and without any public announcement."[29]

But this meeting was on another level of secrecy. Secretaries and wives were told that their bosses and husbands were off for 'duck hunting.' Full names were not used. At close to ten on a cold November night, the last few passengers boarded the last southbound train departing from a nondescript New Jersey rail station. As they began to pull out of the station, the train shuddered to a stop and began to reverse, pulling back into the station. A moment of confusion was settled by a sudden lurch and the slam of couplers—a car had been connected to the back. But what car? When the passengers arrived at their destination, it was gone.[30]

It would be years before anyone knew who boarded that train car that night or what their destination and purpose were. The car belonged to Nelson Aldrich, and its passengers were a veritable who's who of high-power finance. Nelson himself was a business associate of Morgan and the father-in-law of Nelson Rockefeller, future Vice President of the United States. He was also a political kingpin, the Republican whip from Rhode Island of whom Theodore Roosevelt confessed, "Sure I bow to Aldrich. . . . I’m just a president, and he has seen lots of presidents.”[31] Representing the Morgan camp were Benjamin Strong, head of Morgan's Bankers Trust, and Henry P. Davison, senior partner at J.P. Morgan & Co. and Morgan's right hand during the 1907 crisis. Under the banner of Rockefeller was Frank Vanderlip, president of National City Bank of New York. Paul Warburg, partner at Kuhn, Loeb & Co., represented that considerable interest, and in some capacity, the Rothschilds—not to mention the Warburg consortium itself, headed by his brother Max back in Germany. With his intimate knowledge of continental banking practices, Warburg also provided most of the technical expertise. Finally, there was A. Piatt Andrew, the Harvard economist who assisted Aldrich on his tour of Europe and was Assistant Secretary of the Treasury at that time—representing (perhaps) a public interest. Their destination was Jekyll Island, a remote hunting lodge in Georgia. Since 1886, the island had been owned by the Jekyll Island Club, which included J.P. Morgan, Joseph Pulitzer, William K. Vanderbilt, and William Rockefeller.[32] It is here that the Federal Reserve was designed in substance.

If this meeting seems like ancient history: as of 2018, the two largest owners of the New York Fed were Citibank (formerly National City Bank of New York) with 42.8% and JPMorgan Chase (formerly J.P. Morgan & Co.) with 29.5% of shares.[33] Both of these firms had representatives on Jekyll Island, and moreover, the financial houses they represent—Rockefeller and Morgan, respectively—were the prime movers in creating the Federal Reserve.

The Public Relations Campaign

There was only one problem: the utter lack of enthusiasm for their proposals outside of a narrow circle of bankers. In Warburg's opinion, "it was certain beyond doubt, that unless public opinion could be educated and mobilized, any sound banking reform plan was doomed to fail." [34]

To this end, the bankers formed and financed the National Citizens' League for the Promotion of Sound Banking, a nationwide public relations organization intended [according to Warburg] to "carry on an active campaign of education and propaganda for monetary reform, on the principles ... outlined in Senator Aldrich's plan." Although the league appeared to spring from grassroots in 1911, it was from the outset "practically a bankers' affair." Great pains were taken to keep New York's role in the league hidden, given prevailing populist prejudice against Wall Street. Warburg recognized that "it would have been fatal to launch such an enterprise from New York; in order for it to succeed it would have to originate in the West." [34]

With this purpose in mind, the organization was funded by the various clearinghouses. Quotas were assigned: $300,000 to the New York Clearing House, $100,000 to that of Chicago, and the rest of the estimated $500,000 price tag to various others. The league published 15,000 copies of "Banking Reform," a book on currency reform. A fortnightly journal of the same name, with a circulation of 25,000, was also established. They published 950,000 pamphlets of pro-Aldrich Plan statements and speeches and flooded newspapers across the country with "literally millions of columns" of copy. [34]

Passage

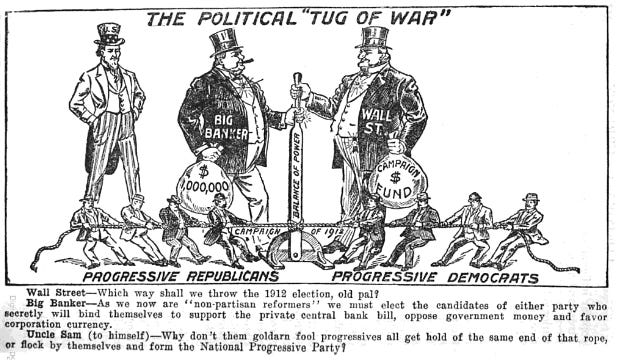

In 1912, Aldrich, the Republican kingpin, brought forward the bill but was defeated; however, the bill was then repackaged and brought forward by Carter Glass of the Democratic Party. Two-party bourgeois democracy in peak form. By the end of autumn 1913, everything was falling into place. In October, the National Citizens League's executive committee shut down, satisfied "that the work of the organization has been practically completed and success has been achieved."[35] On December 19, the Senate passed the bill, and it reached President Woodrow Wilson’s desk on December 23, 1913. He insisted on one change—a Federal Reserve Board in Washington—and signed the bill. [36]

With the advent of elastic currency, capitalist crises could be forestalled. As Forgan, a banker and key agitator within the American Bankers Association, wrote looking back from 1922, "It is a well-known fact that the banks have been and are carrying many industries which would have been forced to the wall, injuring our whole credit structure, had it not been for the fact that the banks in turn have been able to obtain needed currency from the Federal Reserve Banks by rediscounting notes." On top of this, he wrote, it "is difficult to see how we could have weathered the storm of the War."[37] In a word, the Federal Reserve system enabled the preservation of banking interests through successive crises and the financing of WWI.

Furthermore, an important side interest for this same group of powerful bankers was expanding the dollar’s role in foreign trade. Trade at the time was almost entirely financed in sterling through a practice known as banker’s acceptances, in which transactions were guaranteed by a bank, facilitating trade by lowering transaction costs, since instead of actual currency transfer, the accounts could be settled virtually on the books of correspondent banks. This practice was centered in the City of London and converting into sterling cost Americans seeking to expand overseas. Under the National Bank System, American banks could not do this, but with the passage of the Federal Reserve Act, Morgan, Rockefeller, and other interested parties wasted no time forming the American International Corporation, an investment trust aimed at financing overseas development, particularly in Russia and China. It was headquartered at 120 Broadway, an infamous hub which independent researcher Ed Berger has explored in great detail [38]. Of course, this can be understood in line with Lenin’s theory of imperialism based on the export of finance capital. But in hindsight, this development also marks the start of the dollar’s march to global monetary supremacy.

Conclusion

Since the 2008 crisis and the bailouts that followed, the Fed has come under renewed scrutiny. Libertarians are at the forefront, calling to “end the Fed.” When libertarians argue that we no longer have free-market capitalism and that establishment finance, in collusion with the state, rigs the economy, they are diagnosing the problem correctly. However, when they prescribe a return to the free market, they are not being realistic. What they propose is impossible because their main obstacle would not be government intervention but the monopolies themselves. To break up the monopolies, you would have to expropriate them, meaning any path back to a truly free market would have to take a detour through socialism. Even if we assume this is possible and that free-market capitalism was preferable, Lenin already made the decisive and final point in 1916:

…suppose, for the sake of argument, free competition without any sort of monopoly, would develop capitalism and trade more rapidly. Is it not a fact that the more rapidly trade and capitalism develop, the greater concentration of production and capital which gives rise to monopoly? And monopolies have already come into being - precisely out of free competition. [39]

There is no way back. Free-market capitalism has passed away and will not return. Faced with instability, falling profits, and cyclical crises, the archons of finance capital themselves chose socialism—exactly as Marx, Engels, and Lenin anticipated. It is this insight that made their socialism scientific. Only this strange mutation was hardly accounted for: that a corpse could continue walking for so long, animated by military expenditure, imperialist financial intrigue, and bank bailouts—none of which would be possible without the dollar's key currency position and the corresponding license to create endless fiat money. It is the image of a corpse made to walk by the very worms beneath its skin. Corruption becomes the living soul of a dead body. It is truly, in the tired phrase of a bankrupt movement, “socialism for the rich.”

Footnotes

[1]Tucker, Marx-Engels reader, 448-454

[2] Marx, Capital V1, Chapter Three: Money, Or the Circulation of Commodities

[3] Boston University and Perry Mehrling, “Exorbitant Privilege? On the Rise (and Rise) of the Global Dollar System” (Institute for New Economic Thinking Working Paper Series, January 9, 2023), https://doi.org/10.36687/inetwp198.

[4] Marx, Capital Vol III, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1894-c3/ch27.htm Marx is referring specifically to the formation of giant joint-stock enterprises, and the separation of ownership and management (almost precisely along the lines Berle and Means would later famously describe) attending. It is Engels, in an editorial note, who makes explicit the connection to trusts and cartels, which he describes as “second and third degree of stock companies.” Considering that trusts and later holding companies allow corporations to own stock in other corporations akin to how joint-stock companies allowed individuals to do so, one can see plainly what Engels means.

[5] Engels, Socialism, Utopian and Scientific

[6] Friedrich Engels (Neue Zeit, Vol. XX, 1, 1901-02, p.8)

[7] Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism

[8] Bensel, Yankee Leviathan: The Origins of Central State Authority in America, 1859–1877

[9] Gische, David M. “The New York City Banks and the Development of the National Banking System 1860-1870.” The American Journal of Legal History 23, no. 1 (January 1979): 21. https://doi.org/10.2307/844771.

[10] Broz, J. Lawrence. 1999. “Origins of the Federal Reserve System: International Incentives and the Domestic Free-Rider Problem.” International Organization 53 (1): 39–70. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899550805

[11] Allen, F.L., G. Morgenson, and M.C. Miller. The Lords of Creation: The History of America’s 1 Percent. Forbidden Bookshelf Series. Open Road Integrated Media, Incorporated, 2017. https://books.google.com/books?id=4fwnswEACAAJ. P110

[12]Lowenstein, Roger. America’s Bank: The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve. New York: Penguin Press, 2015. p 58

[13]Lowenstein, Roger. America’s Bank: The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve. New York: Penguin Press, 2015. p 59

[14]Allen, F.L., G. Morgenson, and M.C. Miller. The Lords of Creation: The History of America’s 1 Percent. Forbidden Bookshelf Series. Open Road Integrated Media, Incorporated, 2017. https://books.google.com/books?id=4fwnswEACAAJ. p111

[15]Allen, F.L., G. Morgenson, and M.C. Miller. The Lords of Creation: The History of America’s 1 Percent. Forbidden Bookshelf Series. Open Road Integrated Media, Incorporated, 2017. https://books.google.com/books?id=4fwnswEACAAJ. P109

[16]Chernow, Ron. The House of Morgan, p 105

[17]Spence, Richard B. Wall Street and the Russian Revolution: 1905-1925, p42

[18]Chernow, The House of Morgan, 109

[19]Chernow, The House of Morgan, 110

[20]Chernow, The House of Morgan. 166-67

[21]Chernow, The House of Morgan. 166-67

[22]Greider, William. Secrets of the Temple: How the Federal Reserve Runs the Country. Simon and Schuster, 1989. P278

[23]Lowenstein, Roger. America’s Bank: The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve. New York: Penguin Press, 2015. 68

[24]Lowenstein, Roger. America’s Bank: The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve. New York: Penguin Press, 2015. 71

[25]Chernow, The House of Morgan, 173

[26]Dewald, William G. 1972. “The National Monetary Commission: A Look Back.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 4 (4): 930. https://doi.org/10.2307/1991235.

[27]Chernow, The House of Morgan, 173

[28]Chernow, The House of Morgan, 173

[29]Fisher, Keith. 2022. A Pipeline Runs Through It: The Story of Oil from Ancient Times to the First World War. Penguin UK. 389

[30]Griffin, The Creature from Jekyll Island, 4-5

[31]Lowenstein, Roger. 2015. America’s Bank: The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve. New York: Penguin Press. 43

[32]https://web.archive.org/web/20220127084144/https://www.jekyllisland.com/history/timeline/

[34]Broz, J. Lawrence. 1999. “Origins of the Federal Reserve System: International Incentives and the Domestic Free-Rider Problem.” International Organization 53 (1): 39–70. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899550805

[35]Kolko, Gabriel. 1977. The Triumph of Conservatism: A Reinterpretation of American History, 1900 - 1916. 1. Free Press paperback ed. American History. New York: The Free Press. 245

[36]Greider, William. 1989. Secrets of the Temple: How the Federal Reserve Runs the Country. Simon and Schuster. 277

[37] Forgan, James B. 1922. “Currency Expansion and Contraction.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 99 (1): 167–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271622209900123.

[38] Broz, J. Lawrence. 1999. “Origins of the Federal Reserve System: International Incentives and the Domestic Free-Rider Problem.” International Organization 53 (1): 39–70. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899550805

and

https://substack.com/home/post/p-142724023

[39] Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism

RTSG does great things

I loved the part about the invading socialist society. It really is objectively true at this point and beyond any reasonable doubt. I think a lot of our "marxist" opposition are in denial about this. You'd think they would realize that it clearly vindicates Marx, Engels, Lenin.