The Simple Truth of Economics

Explaining the obvious to anyone who isn't a salesman of ideology

John Maynard Keynes once warned that the problem of economics is not complexity, but rather dogma, writing that “The ideas which are here expressed so laboriously are extremely simple and should be obvious. The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones, which ramify, for those brought up as most of us have been, into every corner of our minds.” Almost 90 years have passed since this statement, yet economics remains static. Almost all university students are taught the exact same curriculum with no change or critical thinking involved, only laws. After all, this is the central claim of economics: to have provided “scientific laws” regarding the economy. Nothing can be further from the truth.

Supply and demand curves, or Marshallian scissors as they are often called, are imprinted into the minds of every economics student as fundamental truths. An increasing supply curve, and a decreasing demand curve, providing this sanitized, clean, and simple understanding of economics; and simple answers to almost all contemporary problems in the economic sphere.

This graph forms the basis of much of policy-making around the world, yet its simplicity of it does not accurately describe the actual world.

Mathematics for Utilitarians

The origins of current orthodox economic thinking does not start with Alfred Marshall - or Adam Smith as some erroneously argue - as is often taught in economics courses, it rather starts with the early utilitarians, specifically Jeremy Bentham. The most basic assumption made in economics through which we can aggregate from - the utility-maximizing individual - finds its origins in Jeremy Bentham’s writings. Bentham wrote in his book, Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, that “Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do. On the one hand the standard of right and wrong, on the other the chain of causes and effects, are fastened to their throne. They govern us in all we do, in all we say, in all we think: every effort we can make to throw off our subjection, will serve but to demonstrate and confirm it… The principle of utility recognizes this subjection, and assumes it for the foundation of that system, the object of which is to rear the fabric of felicity by the hands of reason and of law. Systems which attempt to question it, deal in sounds instead of sense, in caprice instead of reason, in darkness instead of light…” Maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain are thus the very core of human existence. The interests of the community are therefore only the aggregate of pleasure maximizing individuals: “The community is a fictitious body, composed of the individual persons who are considered as constituting as it were its members. The interest of the community then is, what is it?—the sum of the interests of the several members who compose it.” Bentham had developed neoclassical economics 250 years before Marshall was even born! All neoclassical economics did was provide a mathematical basis for Bentham’s assertions.

Conventional economic theory starts with a measure of the satisfaction that each individual receives from his consumption, measured in “utility”. It should already be obvious the problem with this logic, attempting to develop an objective measure of a very subjective experience, but for the sake of the explanation, we will go ahead with assuming we can indeed measure it as such.

In the above diagram, one piece provides 30 utility, with each following unit providing a smaller amount of utility. This is described in economics textbooks as the Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility, in which each extra piece provides more utility, but each new one provides less than the old one. You can add as many different products for consumption as possible to this and find what combination of each provides the most utility for the consumer. However, there is an inherent limit with this, as when it comes to graphing this phenomenon, it can only be done with no more than two different products. Translating a utility table between two different products into a 3D graph will provide the following illustration, which we can then derive a contour map from. The contours provide us with what economists call “indifference curves”, each curve telling us the different combinations of two goods which can be used in order to achieve the same utility.

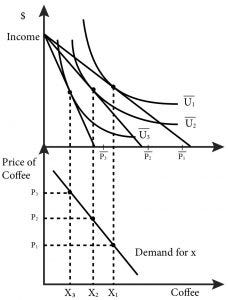

Now, it should be obvious that without some constraint, an individual would consume and infinite amount of each good, which is why a budget constraint exists. The budget constraint limits what combination each consumer can purchase. The point at which the highest indifference curve (the one which provides the most utility) intersects with the budget line is the point that a rational consumer will choose, as it is both feasible and utility maximizing. The famous demand curve then follows from this, as it is simply the aggregation of millions of different indifference curves and budget lines, as can be seen in the figure below:

The higher the indifference curve, the more utility it provides; the opposite is also true. The indifference curves follow certain laws in order for the consumer to be acting rationally, which Paul Samuelson defined as:

Completeness: When given two combinations of goods A and B, a consumer can decide which one he prefers. So A > B, B > A, or A = B (he can get the same degree of satisfaction from both combinations, in which case he is indifferent).

Transitivity: If A is preferred to B, and B is preferred to C, then A is preferred to C.

Non-satiation: More is always preferred to less

Convexity: The marginal utility a consumer receives from each commodity falls with additional units consumed.

This is when we run into the biggest issue with demand curves: the assumptions it makes with regard to human behavior.

Reinhard Sippel has produced perhaps the best experiment with regard to understanding neoclassical theory as applied to reality. In his paper titled “An Experiment on the Pure Theory on Consumer Behavior”, Sippel tested consumers to see if they act according to the laws described by Samuelson. He provided his test subjects with a set of 8 commodities to choose from, along with a budget and a set of relative prices.

The experiment would then be repeated ten times with ten different prices and with only one subject entering the lab at a time - so as not to be influenced by other subjects - to understand what this reveals to us regarding human consumption patterns. He would be asking the subjects to choose any combination they could afford, which already shows an obvious error with neoclassical reasoning. There can be a total of 16.7 million different combinations that they have to compare to decide which is best, and while most will be ruled out by the budget consideration, even if 99% could be ruled out, that will leave 1600 different combinations left to choose from. Steve Keen provides an interesting analogy to what this means: “The neoclassical definition of rationality requires that, when confronted with this amount of choice, the consumer’s choices are consistent every time. So if you choose trolley number 1355 on one occasion when trolley 563 was also feasible, and on a second occasion you reversed your choice, then according to neoclassical theory, you are ‘irrational.’

Nonsense. The real irrationality lies in imagining that any sentient being could make the number of comparisons needed to choose the optimal combination in finite time. The weakness in the neoclassical vision of reality starts with the very first principle of ‘Completeness’: it is simply impossible to hold in your head – or any other data storage device – a complete set of preferences for the bewildering array of combinations one can form from the myriad range of commodities that confront the average Western shopper…”

As Sippel would find out, barely any of the subjects acted in accordance with the laws of rational behaviour; in the first experiment, 11 out of 12 test subjects acted against the laws of rationality, and in the second 22 out of 30 acted in violation of the laws. Nonetheless, Sippel attempted to defend neoclassical theory in the face of this obstacle, contending that the consumers simply couldn’t distinguish the utility between different bundles “It might be the case that the difference in ‘utility’ or satisfaction between a chosen bundle and another one revealed preferred to it is, in fact, hardly noticeable for the subject. We might then regard the inconsistency of not choosing the seemingly preferred bundle as being of minor importance.” He attempts to solve this by essentially making the indifference curves thicker. This meant that for the same price level, multiple bundles can provide the same utility; this did greatly reduce the number of violations, but also implied that the choice between different bundles that maximize utility is completely arbitrary and random, again violating Samuelson’s laws.

Despite his clear bias towards neoclassical economics, Sippel does concede that the evidence supporting neoclassical theory is very thin, writing that “ We conclude that the evidence for the utility maximisation hypothesis is at best mixed. While there are subjects who appear to be optimising, the majority of them do not. The high power of our test might explain why our conclusions differ from those of other studies where optimising behaviour was found to be an almost universal principle applying to humans and non-humans as well. In contrast to this, we would like to stress the diversity of individual behaviour and call the universality of the maximising principle into question.”

As should’ve been already clear to most people on an intuitive level, Rational Choice Theory cannot account for human behaviour, which is varied, diverse, and often without reason, based rather on habit and rule of thumb. As anyone working in marketing would tell you, human behaviour is easy to manipulate. However, there are good reasons to believe in a downward-sloping curve and inverse relationship between quantity and price, so how do we reach this without falling into such obvious fallacies?

What Now, Jack?

We can develop a new model for consumption that can reach the same conclusions the neoclassical model hopes to achieve, without referring to ridiculous assumptions such as “perfect knowledge”, “rational choice”, “utility maximization”, etc. That being, a downward sloping demand curve, the elasticity of greater than 1 for luxury goods, and elasticity of less than 1 for necessity goods. This has already been illustrated in the works of Anwar Shaikh.

We will create two goods: a necessity and a luxury good

The necessary good, by definition, cannot go down to zero, for example, your consumption of food or water cannot simply disappear and sustain human life, so it needs to have some minimum level of consumption.

$ x_1$ represents the necessary good, which needs to have some minimum value $x_{min}$.

So the budget constraint can then be represented to exist somewhere between $x_{max}$ and $x_{min}$ where we can define $x_{max}$ as $\frac{y}{p_1}$ where y is income and $p_1$ is the price of the necessary good.

we can then develop three definitional equations from this:

Where $p_1$ is the price of the necessary good and $x_1$is the quantity of it, $p_2$ represents the price of the luxury goods (for which we will assume savings is also a luxury), and $x_2$ the quantity. Although it would be more realistic to think of each element here as a vector with the following notation:

where:

where each dot product is simply the summation of the multiplication of all the different prices of all the different products (both luxury and necessity). However, as the main objective here is communicating ideas with as little math notation as possible, we will be using simple algebraic notation instead of vector notations. We can thus define $x_2max$ and $x_1max$ as follows:

In which $\frac{y}{p_1}$ is the maximum number of necessary goods that can be purchased if all income is spent on necessities, and $\frac{p_1}{p_2}x_{1min}$ represents the minimum expenditure on necessary goods.

We can then graphically represent the three equations, providing us with the following familiar figure:

Note how the maximum amount for a luxury good is not on the complete end of Y axis, as you cannot spend all your income on luxury goods, so it's a much more feasible range. Point A represents some bundle of luxury and necessary goods, which is feasible.

People are very heterogeneous when it comes to their consumption choices. They can vary based on gender, religion, nationality, race, ethnicity, etc. and each will have a different motivation for what their consumption pattern will look like (some will have none!). As we have already established, consumption for necessary goods will fall somewhere between the minimum and maximum. We can represent that proportion as 𝜋, which we can call the average propensity to consume: a measure of how much total income is spent on necessary goods. Anyone who has studied economics before can see that this is very similar to the Keynesian marginal propensity to consume (MPC). All consumers will then have different lambdas, but in the aggregate, it will have a sort of stability, due to emergent properties.

Even if we assume that a variety of models can develop a downward-sloping demand curve (neoclassical representative agent model, Becker model, etc.) and if we can derive the same outcome with a model using far less ridiculous assumptions, it follows from Ockham’s razor that we choose the simpler model which can be derived from equation (1.1) to (1.3) to provide us with the following:

we can then derive the demand for each good from the 4 previous equations:

As you can see, as the price of both commodities increases, the demand will decrease. So, we have successfully derived a downward-sloping demand curve without falling into the fallacies neoclassical assumptions lead us into. While neoclassical logic will necessarily lead to a failure to derive a downward sloping demand curve, just three simple definitions will be enough to derive it without any reference to the motivation of different individuals. We only assume that the aggregate will produce some stable lambda, something anyone familiar with meteorology and particle movement should understand intuitively. For example, imagine we have a glass container to which we add gas, and then measure its pressure at different temperatures. This is known as the Gas Law, which states that there is a relationship between pressure, volume, and temperature, written algebraically as PV=nRT. What is worth noting is that this law applies only to the whole, not to individual particles, as the law was observed before it was discovered that gasses are composed of particles. The macroscopic properties were discovered before the microscopic properties. For those more interested in a more rigorous mathematical formulation of this aggregation problem, I would point you to the Debrue-Mantel-Sonnenschein Theorem, a good exposition of which can be found in Daron Acemoglu’s book Introduction to Modern Economic Growth.

From just three simple definitional equations, we have been able to derive almost all of what microeconomics hope - but fails - to achieve: a downward-sloping demand curve, price elasticities of both necessary and luxury goods. And all of this without having to rely on assumptions regarding the motivations of individual consumers. The microeconomics taught in almost all universities have failed, and this has broader implications than simply the failure of academia. These very assumptions are what informs policy-making around the world in some of the biggest global institutions such as the IMF, the UN, and countless governments around the world. Despite the clear failure of the theory, most economists attempt to introduce failures into the theory in order to account for the actual empirical reality. They start from a position of perfection and then slowly add imperfections until the model reflects the reality: they cannot embrace the reality for what it is. Utilitarianism is their God, and Bentham their prophet.

Dear RTSG,

I am truly inspired by your thorough analysis and insightful research. Your ability to explain complex ideas in a way that even someone with no background in economics or geopolitics can grasp is remarkable, and it makes your perspective incredibly relevant and accessible.

If you don’t mind, I would greatly appreciate it if you could recommend some books for someone interested in learning more about economics and geopolitics. Your expertise in these fields makes your suggestions particularly valuable.

Thank you for your time and for sharing your knowledge so generously.

What is amusing is that in some cases demand rises as a good gets more expensive, of course. As in the upper classes where spending more adds to status...